Ask any motorcyclist why they prefer a bike to a car and they’ll probably tell you that they prefer to be IN the moment rather than looking at life through a window. It’s the same with the safari experience and that’s where Kenya’s conservancies come in.

The majority of visitors explore Kenya’s globally-renowned national parks from the comfort and safety of a safari vehicle. Increasingly, however, there are those who want to leave the safari vehicle behind and get their boots on the ground: to walk or ride across the wilderness.

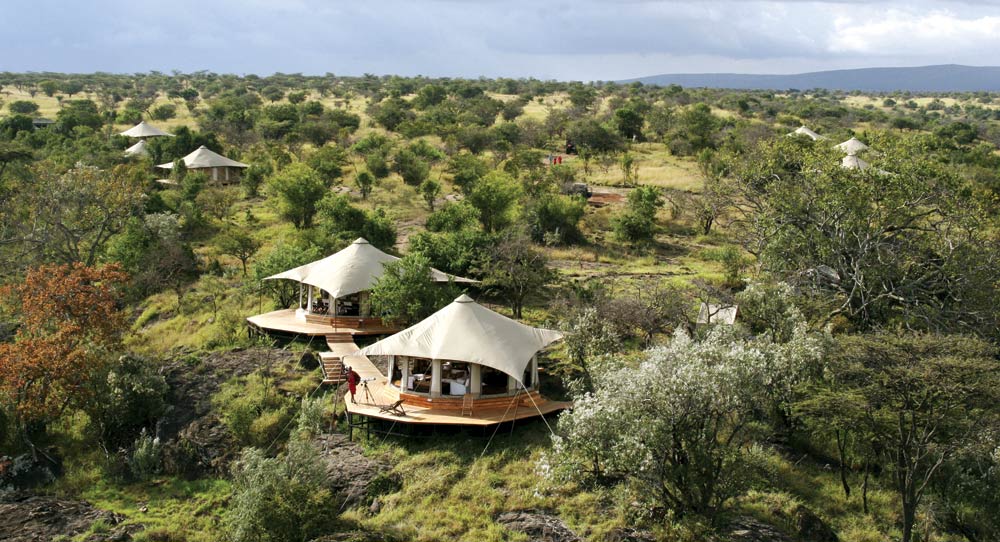

Conservancies are the new frontier of Kenyan tourism.

So, what’s the difference between a conservancy and a national park or reserve?

The quick answer is that, in general, the national parks and reserves are longer-established, some dating back to the 1940s when they were created specifically to protect Kenya’s wildlife and wilderness. They’re also more ‘high-profile’ including such well-known destinations as the Masai Mara, Amboseli, Samburu and Tsavo, amongst their 56-strong ranks. Nationally owned, they are administered by the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), permit no human activity, such as herding, and are generally much more restrictive in the range of activities permitted.

Kenya’s conservancies are a different species. They’re younger, the first one having been established in the 1980s, they’re community-owned and run, and they’re dynamic.

Less restrictions, more experiences

As to restrictions – conservancies only limit the number of camps, lodges and vehicles allowed on to their land. This lowers the environmental and ecological impact of tourism and improves the visitor experience. They don’t however restrict the activities on offer. This means that visitors can enjoy unique safari experiences such as walking safaris, horse-riding safaris, camel safaris or night game-drives (all of which are not allowed by KWS run parks).

Ecologically sound

Typically, the conservancies occupy land either previously held privately or only relatively recently reverted to wilderness. Sometimes the border between a national park and a conservancy might be nothing more than a line of white stones. Consequently, the scenery is the same and the wildlife wander back and forth at will. However the wildlife densities in conservancies are higher, while the numbers of tourists viewing the wildlife are lower. Crucial too, is the fact that the extension of sheltered wilderness has allowed a network of wildlife corridors to be extended across the country. And this means that many animals, such as elephants, can follow the ancient migration routes that they have trodden since the dawn of time.

A powerful partnership between the communities and the tourism industry

Most importantly of all, conservancies are managed according to a model that protects the delicate ecosystem and benefits the landowners themselves.

When, for instance, a group of Maasai people decide to turn their ancestral lands into a conservancy they not only derive an income from visitor fees and accommodation but they can also still use the land to graze their herds. The income can finance schools, health centres and wells – but the land is still theirs for posterity.

Kenya’s conservancies also promote new livelihoods such as bee-keeping or handicrafts, which provide an income for the women of the community. This empowerment has a positive impact on communities and helps prevent negative practices, such as the incidence of child brides and the tendency of impoverished communities to deny education to girls.

Conservancies also use their income to provide training for the growing number of young males unable to find work and to provide the technical skills that ensures the land is well maintained and improved.

Kenya’s conservancies: sanctuary for endangered species

Crucially, the conservancies provide sanctuary for those endangered species such as rhinos that are threatened by poachers and which also can no longer remain in the national parks due to the fact that their numbers have exceeded the ability of the biosphere to support them. And they reduce the incidence of human-versus wildlife conflict by teaching people how to construct predator-proof enclosures and elephant-proof fences.

In the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy for example, the rhino population has grown from an initial 15 rhinos to 169 rhinos today.

The conservancies of the Masai Mara

The Masai Mara offers the perfect case study. It is surrounded by 15 conservancies that protect 450,000 acres of hitherto unprotected land upon which is enacted the world-famous annual migration of the wildebeest. In the greater Trans Mara, the lion population has doubled over the last decade. And 3,000 households have earned more than $4 million annually from tourism.

And the tourist still has the best of both worlds: access to the world-class vistas and world-famous lodges of the National Reserve and the chance to walk the wilderness, ride alongside zebra, or observe a lion pride in solitary splendour. A wilderness win:win.

The conservancy equation

Kenya has lost nearly 70% of its wildlife during the past 30 years.

65% of Kenya’s wildlife live in community and private lands

Kenya has 160 conservancies (4 of which are marine) covering 6.36m hectares, which is 11% of Kenya’s land mass

90% of all endangered hirolas and Grevy’s zebra reside on conservancies, 72% of southern white rhinos and 45% of black rhinos. Incidences of reported human versus wildlife conflict between 2011 and 2015 increased by 86% nationally, but on the private conservancies it decreased by 72%.

For more information, visit: https://kwcakenya.com/

© 2025 Kenya Holidays