Mudanda Rock, Tsavo East

In this feature a member of our travel writing team visits Mudanda Rock, Tsavo East. Kenya’s answer to Australia’s Ayers Rock, Mudanda is a place steeped in ancient history. It’s also very popular with the local elephants.

There’s a stunned silence as we arrive at Mudanda Rock. It’s taken us five hours to get here. And we have hardly encountered another human being or seen a single car in all that time. We’ve traversed valleys painted white-over with blossom where the air is laced heavy with scent. And we’ve driven under skies almost blackened by swirling flights of swallows. We’ve encountered great herds of elephant mining for water in the dry riverbeds, lone kongoni perched atop ant hills, drifts of zebra and squabbles of vultures. But not a single sign of civilization.

We’re in Tsavo East National Park, one of the last great tracts of wilderness on earth. Much of it is so wild, so far off the beaten track, that it’s visited only by the rangers of the Kenya Wildlife Service. Closer to the park gates there’s a tiny circuit of roads bustling with tourism vehicles. But we are not on it.

We’re out on a limb, taking a risk: these rusty-red tracks are treacherous. Some are blocked by trees newly felled by elephants, some by vulturine guineafowl, others have been washed away by torrents of water in the recent rains. Others end abruptly in yawning chasms. But we’re in safe hands, our guide knows this area well; he’s checked out the roads in advance. He’s also a happy man. ‘I can’t remember the last time I visited the rock,’ he says, ‘most visitors don’t have the time to get there.’ He turns around to smile at us, ‘most don’t even know it’s there. You’ve given me a real treat,’ he says. His ‘treat’ is Mudanda Rock.

And we’re sitting in silence. Staring at it.

Mudanda Rock is a step back in time

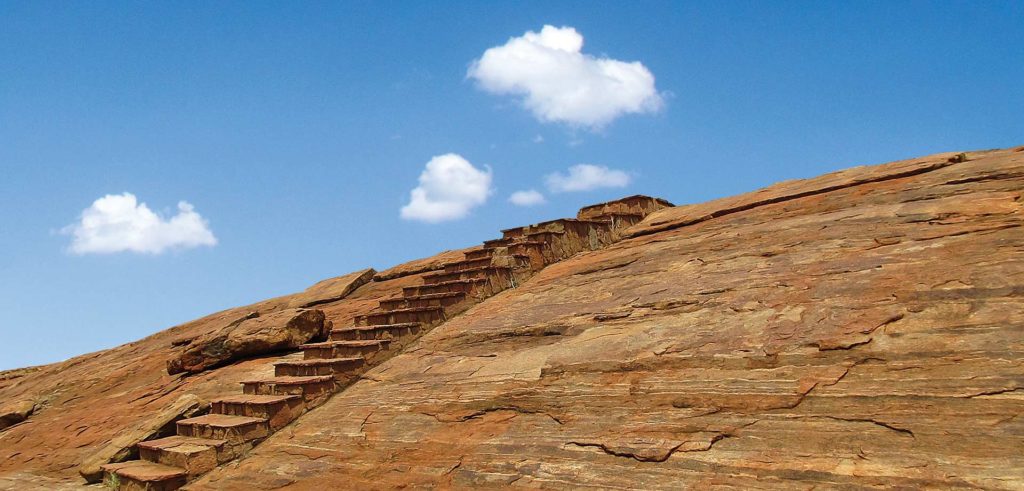

At first glance, it’s underwhelming. A huge whale of pinkish red stone that rises unexpectedly out of the bush with a flight of steps cut into its huge flank. They look like a stairway to the stars. There’s a signboard at the foot of the steps. It tells us that Mudanda Rock is Precambrian basement rock - between 570 and 4,550 million years old; that it’s popular with leopards and elephants; and that thousands of years ago it was used by hunter-gatherers known as the Waliangulu as a place where they dried their elephant meat. ‘That is what ‘Mudanda’ means’ says our guide, ‘the place of dried meat’. We’re mildly diverted, but still underwhelmed. And then we begin to climb the staircase. And everything changes.

Climbing to the top

It’s only when you start to scale the vastness of Mudanda Rock that you realise just how massive it is. Running for 1.5km, it’s like a vast pink runway, a landing strip for the gods. Atop its summit, streaked all the colours of pink and purple, the view over the wilderness is matchless. Here, great natural stone benches rise from the smooth pinkness; some are blood red as though drenched in elephant blood. Time spirals backwards; you can almost sense the presence of the hunter-gatherers.

The hippo pool

On the far side of the rock, the hump metamorphoses into a cliff and drops steeply away into a great pool of water. As we watch, a thin vein of red moves out of the khaki of the bush and makes its way to the water. It’s a herd of elephants. As they near the water, they fan out, each to stake his or her own claim to a particular stretch of water. They’re dwarfed by the immensity of the rock. So are the hippos as they rise to chortle and blow, their little ears spinning like radar dishes.

The residents show up

In the far distance there’s the glint of the Galana River as it snakes along the foot of the Yatta Plateau, the longest lava flow in the world. An agama lizard arrives; his colours flaring orange and blue against the salmon pink of the rock. He’s followed by a troop of baboons. They’re disdainful of us. We don’t belong here and they know it.

As we leave, the elephants arrive

We descend the staircase and regain our vehicle. As we drive away we notice that another herd of elephants has arrived. And with infinite care, one plate-sized foot after another, they’re scaling the rock. The thought comes unbidden: what if they’d met us on top? It’s a thought that must have occurred to many a hunter-gatherer. Many moons ago.

Tsavo East - the facts

Tsavo East National Park (13,747 sq km) is one of Kenya’s oldest and largest parks and lies in a semi-arid area previously known as the Taru Desert. A number of early Stone Age and Middle Stone Age sites have been recorded and there is great evidence of a thriving late Stone Age economy from 6,000 to 1,300 years ago.

The migration of the wildebeest in the Masai Mara

The migration of the wildebeest in Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve is the largest single movement of wildlife on the planet. It's also known as the Greatest Wildlife Show on Earth - with good reason.

The annual migration of the wildebeest in the Masai Mara is a spectacle unrivalled in grandeur. Pure theatre, it is always awe-inspiring, sometimes comic, often tragic. Painted large across the face of the savanna it presents an image that is both breathtakingly beautiful and bitterly brutal.

The Blue wildebeest is also known as the gnu

The blue wildebeest is a large antelope that gets its name from the silvery blue sheen of its hide. Looking rather as if a can of paint has been emptied over it, it has shaggy festoons of black hair that tumbles from its head and along its back.

Between the end of July and November, over one-and-a-half million blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), accompanied by half again as many zebras and gazelles, migrate from the short-grass plains of Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park to fresh pasture in the grasslands of Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve.

Towards the end of October, the wildebeest begin crossing back into Tanzania. The actual timing of the migration, however, is dictated by the weather and does not always run to schedule.

A new-born wildebeest learns to walk in minutes

Some 500,000 wildebeest calves are born in February and March of every year. Weighing up to 22kg at birth, they learn to walk within minutes. At maturity, a wildebeest can run at up to 80 kilometres per hour.

The famous Mara River crossing

Moving in groups of up to 20,000 at a time they thunder across the plateau hesitating only briefly to cross the Mara River. And here many fall prey to the waiting crocodiles which drown their prey by clutching them in their strong jaws and pulling them below the water, twisting them to break off bite-size pieces. A crocodile can lunge more than half of its body length out of the water to grab a potential victim and can also use its tail as a secondary weapon.

Swarm intelligence

While the migration may seem like a chaotic frenzy of movement, research has shown that a herd of wildebeest possess what is known as ‘swarm intelligence’. This means that the wildebeest systematically explore and overcome an obstacle as one entity. However, because wildebeest have no natural leader, the migrating herd often splits up into smaller herds. These also circle the main, mega-herd, going in different directions.

Wildebeest sightings in the Masai Mara are guaranteed

As well as featuring in the main migration, Kenya has its own private migration. This is known as the Loita migration, which commences in April. At this time, some 30,000 wildebeest migrate from the conservancies to the north of the Masai Mara National Reserve to the mineral-rich soils of the Loita Plains. And they linger there until June when they move back to the private conservancies.

A Maasai village visit

One of the highlights of a visit to Kenya is the chance of experiencing an authentic Maasai village visit. Such visits will generally be arranged by your tour guide or lodge and are well worth doing. This feature aims to give you an idea what to expect of your visit.

Once outside the boundaries of the Masai Mara National Reserve, the landscape changes. We drive past small settlements, people walk alongside the road; donkeys graze and little bands of children turn to watch us go by. We turn off the road and bump along a track until we come to a high brushwood fence.

A smiling Maasai welcome

A group of young men wait by a break in the fence. They’re dressed in traditional Maasai costume – red, plaid, shuka cloaks, simple sandals made from old car tyres, known as ‘thousand milers’, strings of beads wound around their chests. Our driver calls out a greeting and the young men approach to welcome us. Their English is perfect; their smiles are wide.

We move on into the village or boma (enclosure). It’s a large circular enclosure containing a central area of bare mud. Around the perimeter are perhaps eight or nine low huts with mud walls and flat brushwood roofs. A few scantily clad children peep around corners – eyes large. A yellow dog with a curled tail sleeps in the sun.

We meet the villagers

We are introduced to the chief of the village and now, as if beckoned by some unseen signal, people emerge. Women cradling babies, old men leaning on long sticks. But there are no warriors and no younger women. The reason soon becomes apparent – they have been getting into their dance costumes.

The warriors approach in a long line, their heads dipping as they pace rhythmically forward raising and lowering their spears as they come.

And then the dance begins. In the centre of the boma, the maidens sing, their voices high-pitched, reed-like and surprisingly loud. They move in a stamping, swaying dance – like so many brilliantly coloured butterflies.

Maasai jumping

The young men take the stage. Their song is deep and reverberating. They form a semicircle and one by one, step forward and jump high into the air. It’s uncanny just how HIGH they can jump. ‘The current Maasai record is eight feet’, says our guide as an aside.

Naturally, we're encouraged to have a go ourselves.

Bartering for beadwork

Almost as quickly as it began, the dance ends, and the colourful crowd moves off. ‘Now to the market,’ says our guide. Beyond the rough fencing of the boma, a makeshift market has been set up – and here the people from the surrounding bomas have set up their display.

Some ladies sit on the ground, others have simple stalls – and the display of beadwork is stunning. There are necklaces and collars, beaded walking sticks and beaded belts. Every lady strives to thrust her own wares forward. It’s utterly chaotic and superbly colourful. Cameras whirr. The ladies don’t speak English so the chief translates. We’re expected to barter and, though timid at first, we enter into the swing of things. Finally, laden with belts, beads, shields, gourds and fly-whisks we return to our vehicle. But we’re not alone. We’re escorted by the ladies, the dancers, the warriors, the toddling children and the yellow dog.

A Maasai village visit is an experience and a privilege

Reluctantly we depart. We’re silent in the vehicle. Absorbing it all. For perhaps 45 minutes we have been welcomed into another realm – one so entirely unlike our own that we are simultaneously humbled and uplifted. It’s an experience and a privilege. And one certainly not to be missed.

Climbing Mount Kenya

Thousands of people enjoy climbing or trekking up Mount Kenya every year. Most reach only Point Lenana (4,985 m) because to go higher requires more advanced climbing skills. Some people make the summit in 3 days, others in 4-5 days: it all depends on the route and the degree of altitude acclimatization required. All agree, however, that for variety of landscape, wildlife, views and just sheer exhilaration – it’s one of the world’s most stunning climbs. Here we give an overview of the three most popular routes to Point Lenana.

About Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya is the second highest mountain in Africa and its stunning natural wilderness and forest has been inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The mountain is an ancient extinct volcano, last thought to have been active around 2.6 million years ago. There are 12 remnant glaciers on the mountain, though all are receding rapidly. On the lower slopes, the mountain comprises dense bamboo and rainforest changing to Afro-Alpine moorland at higher elevations.

Climbing Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya’s highest peak is Batian (5,199m), followed by Nelion (5,188m) and Point Lenana (4,985m). Batian and Nelion require technical climbing skills but Point Lenana is a trekkers peak, which can be reached in 3-5 days depending on the route. However, a reasonable level of fitness is still required: one should be comfortable walking for 6-8 hours per day. And trekkers should also ensure they allow adequate time to adopt a sensible pace and avoid acute mountain sickness.

Naro Moru Route

This is probably the most popular route, being the shortest up the mountain – it can be ascended in 3 days. Many guests base themselves at the popular Naro Moru River Lodge.

The Park entrance (2,400m) is 17km from Naro Moru town, to the west of the mountain. From the entrance, a paved road leads to the Met Station (3,050m) where the trek begins. (It is recommended that trekkers who are not used to high altitude should spend the first day walking from the Park entrance to the Met Station, rather than driving, in order to acclimatize.)

From the Met Station, you reach a steep, marshy section known as the “vertical bog”. The route continues through open moorland to the crest of a ridge overlooking the Teleki Valley, then descends to the valley floor and up again to Mackinder’s Camp (4,200m). The trekking time from the Met Station is approximately 5-6 hours. Usually an acclimatization day follows.

The next part of the journey is a steep, winding route on loose ground to reach the Austrian Hut, or Top Hut (4,790m) at the foot of the Lewis Glacier. It is then onward to Point Lenana, with the added excitement of a ‘via ferrata’ – or fixed lines – to help you scamble up the summit ridge.

The Chogoria Route

The Chogoria route is widely regarded as the most picturesque of the routes up the mountain with several lakes and tarns to explore. There are no huts however, so trekkers and climbers need to be prepared for camping. It is also a longer route than Naro Moru, usually taking 5 days in total.

The route sets off from Chogoria town, to the east of the mountain. From here it is a 30km drive to the Park entrance (3,000m). Accommodation is available at the Meru Mount Kenya Lodge.

The path continues through giant heather and forest to Chogoria Road Head (3,300m) and then across the north side of the Gorges Valley to Hall Tarns (4,230m), offering spectacular views over the valley and Lake Michaelson. The hiking time from Chogoria Gate to Hall Tarns is approximately 6-9 hours.

The path from Hall Tarns continues past the Simba Tarn and Harris Tarn to Point Lenana (4-5 hours).

The Sirimon Route

The Sirimon Route approaches from the north and is another walking route that reaches Point Lenana. It is probably the easiest of the three routes and also offers spectacular scenery. It usually takes 5 days.

From the park gate, a road leads to Old Moses Hut and Judmaier Camp (3,350m). The track then climbs 300m to a communications station and then crosses moorland and ridges, dropping down to the Liki North River and then up a ridge to the Mackinder Valley. The path continues to Shipton’s Cave and then climbs steeply to Shipton’s Camp (4,250m). The route then ascends to Harris Tarn from where Point Lenana is reached.

Getting down

Having reached Point Lenana and taken in the views, there are various options for a descent route: the stunning Chogoria route is popular, but quicker descents can be made on the Sirimon route or the Naro Moru route.

Climbing Mount Kenya - more information

For information on climbing routes, visit the Mountain Club of Kenya website: www.mck.or.ke

Note: the MCK is a members-run, non-profit club and does not offer guiding services directly.

Horse riding in Kenya

Imagine galloping across the plains alongside a herd of giraffe, riding up to an elephant, or watching the migration unfold from your saddle. Enjoying a short ride or a full horseback safari in Kenya is an exhilarating experience and a very popular choice.

Rides for all abilities

Kenya has a long history of conducting horse riding safaris. As well as the specialist operators, many of the lodges, hotels and private reserves have their own stables. Game viewing on horseback is a very special experience. And it benefits from the fact that many animals in the wilderness don’t see horses as a threat and allow them to get extraordinarily close.

Rides can be as short as a few hours, a full day (with a picnic lunch), or a full safari for a week or more. If you’re riding around the grounds of a lodge, no vetting is required but if you’re going out into the wilderness however, you will typically be assessed to grade your proficiency. And you will always be accompanied by a guide – known as a syce in Kenya.

Many of the lodges offer family rides using horses which are known to be docile. Often the younger members of the family will be attached by a leading reign to the syce.

Where to ride

The most popular horse riding safari destinations in Kenya are: the Masai Mara conservancies; Laikipia and the central highlands; and the Chyulu Hills, between Tsavo and Amboseli. In these beautiful areas you can ride for days, taking in the scenery, getting close to the wildlife and reaching areas inaccessible by vehicles.

Depending on the exact itinerary of your riding safari, accommodation will be provided in permanent or mobile bush camps (with full safari kitchens, mess tent, WCs and hot showers), or in luxury lodges. Often a combination of both is used – so as to allow days of rest and pampering between the rides. Such a safari also offers plenty of scope for guided walks, ornithology, riverside sundowners or bush campfires.

Horses for courses

As well as riding, you can take time out from your Kenyan safari to enjoy some equine sports. Around central Kenya, you can take in some world-class polo matches – polo being a sport in which Kenya excels. If you’re in Nairobi, you can place a bet while enjoying the style and pace of Nairobi Racecourse, rated as one of the world’s most beautiful racing venues.

Kenya horse riding safaris - find out more

For a short horse-ride in Kenya you will be issued with a hard hat. If you’re planning on doing a longer ride (or a full riding safari), you will also be able to access boots, gloves and other equipment. Check with your tour organisor in advance.

The following operators and accommodation providers have an excellent reputation for conducting horse riding safaris.

Offbeat Safaris

Safaris Unlimited

Great Plains Conservation - Ride Kenya

Want Inspiration in your Inbox?

Sign up for FREE to receive our monthly e-newsletter with features

and ideas to help you plan your Kenyan adventure

© 2025 Kenya Holidays