Sundowners on Pride Rock

Pride Rock is not easy to reach. But the road to triumph is always tough, especially in the world of Walt Disney where many a frog must be kissed to reveal a prince.

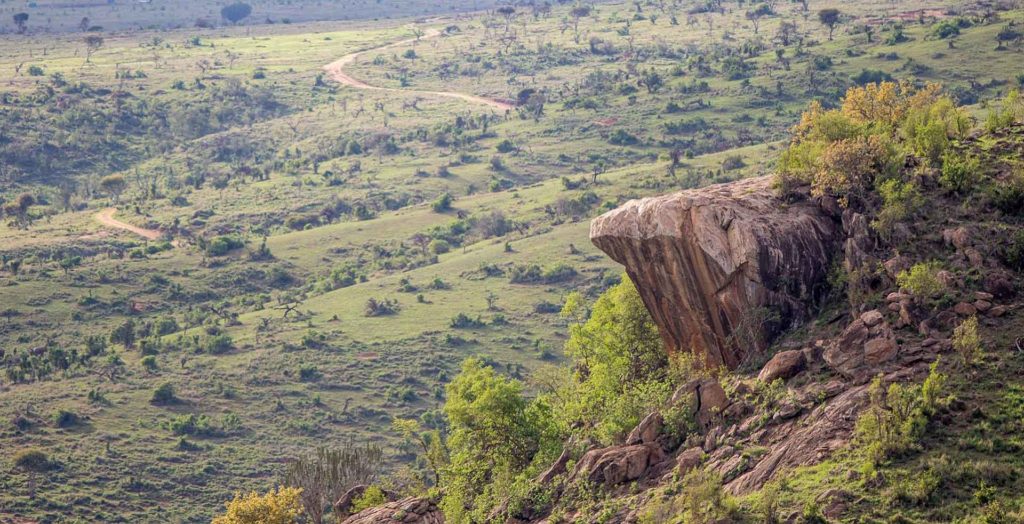

In this case, we’re in the wilderness lands of Laikipia, Kenya’s heartland, following a tortuous path through thick khaki-coloured grass. It’s wide enough only to put one foot in front of another; and it winds down into a dry riverbed where we must slither and scramble over outcrops of quartz rock glinting gold in the fading light. From here it’s a steep uphill climb to the great crag of rock that rears up against the darkening sky. We’re at altitude, breath is short and we keep our eyes on the heels of the person in front.

‘Everything you see exists together in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance, and respect all the creatures, from the crawling ant to the leaping antelope… When we die, our bodies become the grass, and the antelope eat the grass. And so we are all connected in the great Circle of Life.’

Mufasa in the animated film, The Lion King

The inspiration for The Lion King

Suddenly, or so it seems, we’ve arrived at the great grey rock. It’s hunched on the landscape like a gigantic frog about to leap. Just one short jump across the mouth of a deep crevice and we’re on its broad, flat surface. A vast apron of rock, it’s scarred by cracks and dimpled by puddles of water. Above us the darkening sky is pinpricked with the first diamond scatter of stars. Below us, the bush rolls away in great waves of gunmetal grey.

In the far distance rise the massive shoulders of Mount Kenya, her jagged central turrets silhouetted against the sky. There’s a howling wind blowing up here; and it’s pushing us towards the edge of the rock from which it’s a murderous free fall to the ground below. It’s a very famous edge; and a very famous fall; because this is Pride Rock, the inspiration for the Walt Disney Epic, The Lion King.

The Pride Lands

This is a rock that’s familiar, in cartoon form at least, to literally millions around the world. It was for this rock that Simba the lion cub fought his battles. From this rock, that his father, King Mufasa, ruled the Pride Lands until he was murdered by his wicked brother, Scar. Atop this rock that was enacted the famous fight scene between Simba and Scar. And from this rock that Scar fell to his death in the jaws of the hyenas below.

It was in 1991 that the Walt Disney production team first came here. In Hell's Gate National Park, Kenya’s dramatic geothermal park, they’d found the inspiration for their characters: the Pride lions, Pumbaa the warthog, Rafiki the monkey, Zazu the hornbill and the three wicked hyenas. But it was only here, in Borana, that they finally found the stage upon which their great drama, loosely modeled on Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, would be enacted. It was an epic choice: The Lion King was to become the most successful traditionally animated film of all time.

Released in 1994, The Lion King won two Academy Awards and the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture. The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride came out in 1998. The musical stage-play, The Lion King debuted in 1997 and is now the fifth longest running Broadway show. A photo-realistic animated remake of the film was released in 2019, marking the 25th anniversary of the release of the original film.

Kenya's most famous sundowner spot

Today, Pride Rock is famous for quite a different reason: it’s the most popular sundowner spot on the Borana Conservancy, in the heart of Laikipia, northern Kenya. In fact it’s so popular that it has its own Facebook page and must be booked in advance. We’ve been lucky. Tonight Pride Rock is vacant and we have its rocky stage all to ourselves. Now it is time to enact the famous Kenyan sundowner tradition, which dates back to the early days of the colonial era hunting safaris. The canvas bags are unpacked, an impromptu bar is set up. There’s a tray of canapés still warm from the kitchens of Borana Lodge and warm wraps, scarlet Maasai shukas, are handed out as we sit on a ledge to watch the sun go down over the wilderness lands of Laikipia.

Tomorrow, at dawn, others will come to Pride Rock to practice yoga as the great ball of the sun rises in the sky. Later, horse-riders might gather in its shade when their safari ride is over. In the late afternoon, walkers will gather here at the end of their guided walk. And as the curtain falls on another day, others will sit on Simba’s rock to look out over the Pride Lands.

Overhead shines a vast arc of stars. The crescent moon hangs like a bauble on the last vestiges of cloud. It’s time to pick our way back down the darkening path to the safari vehicle. Reluctantly, we turn our back on the Pride Lands. Suddenly there’s an eerie whoop, whoop, WHOOP in the night.

The hyenas are coming.

How Kenya is saving the African Wild Dog

African wild dogs, also known as painted wolves or Cape hunting dogs, have seen drastic population declines over recent decades. In this article from 2017, we looked at Kenya's efforts to save the African wild dog from extinction, and discovered how these endangered animals are beginning to recover here.

Painted wolves in the morning

The early mornings are celestial on the Athi Plains about an hour’s drive south of Nairobi. Clear blue skies, cloud free; rolling savannah backed by quartz-glinting hills. Far away the occasional gleam of the ‘Lunatic Line’, the colonial railway track that winds all the way down to Mombasa. And, if you’re very lucky, there might be a guest appearance by Mount Kilimanjaro. Silver grey, she appears and disappears like a vast pink mirage; a giant Christmas pudding lilac-topped with snow.

The ideal territory for African Wild Dogs

There’s a plaintive keening of hornbills and the bubbling coo of the emerald spotted wood doves. But this is no national park. Not even a reserve or a conservancy. It’s just a vast swathe of land once teeming with wildlife, later converted to sprawling colonial cattle ranches. But both are gone now. Africa has taken back her own and now the Athi Plains are just mile upon mile of scrubby bush punctuated by an ever-increasing number of settlements. They do, however, provide ideal territory for African wild dogs, or ‘painted wolves’.

The ears arrive first, pricked in the long grass. Round and black like so many radar dishes. Heads appear. Then there’s a cautious peering and sniffing. A decision is communally made: two humans walking in the bush don’t present a threat. And the pack of wild dogs emerges.

The liquid pack

At first you wonder if it’s a pack of mongrel dogs. Then you realize that mongrels don’t look like this. They’re not so rangy, so watchful, so much of a cross between a wolf and a hyena. Nor are they painted in such fantastic colours, splashed with rust and white; dripped with black and grey – a gorgeous hybrid print of wildebeest and leopard. And domestic dogs don’t move with one accord, flowing over the landscape as if all part of the same organism.

The wild dogs don’t stay long. They’re on a mission of their own. The signal is given and the liquid pack, now an amorphous mass of black, brown and rust so brilliantly camouflaged that it appears like a brief shadow on the landscape – is gone.

Under threat across Africa

But we have been immensely privileged. The African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) is one of the most endangered creatures on the planet. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, there remain only around 6,000 across the entire African continent. And their numbers are plummeting. It’s not just that these whimsically beautiful beasts are affected by diseases such as rabies or canine distemper, both of which are passed on to them by domestic animals; or that their range has been radically encroached upon by man. It’s also that farmers across Africa are killing them in the belief that the dogs have killed their livestock. In reality, however, wild dogs typically hunt only wild animals.

But there’s a greater threat: recent research has revealed that the African wild dog is being threatened by climate change. A group of scientists from the Zoological Society of London, the University of Johannesburg and the Botswana Predator Conservation Trust contend that rising global temperatures have affected the dogs’ ability to hunt and, by inference, to produce healthy pups. Extinction looms.

Kenya's efforts to save African wild dogs

In Kenya, however, there is hope. The Kenya Rangelands African Wild Dog and Cheetah Project has devoted over 15 years to concocting a cocktail of measures designed to allow the African wild dogs to survive in a human-dominated landscape. Domestic livestock has been inoculated against rabies and pastoralists have been taught how to construct more efficient bomas (pens) for their livestock. They’ve also been encouraged to revert to the old ways of land use whereby land is set aside for dry season grazing thus leaving areas in which the dogs can run free. Farmers have also been persuaded to donate land for ‘wildlife corridors.’ And in return they’ve been given a share in the proceeds of tourism that the wildlife attracts.

Outreach programmes have been established to monitor the movement of the dogs by means of radio tracking collars or scouts. And local herders are alerted to the fact that a pack of wild dogs are in the neighbourhood and that their vigilance should be increased.

The results have been startling. Over the last decade the numbers of African wild dogs in the Samburu-Laikipia region have increased eight-fold. This is good news. Because not only does the wild dog provide a supreme example of the efficiency of the pack – which works with one accord and for the good of all – but also because the wild dog can trace its ancestry back 40 million years to a creature known as Miacis, which was the ancestor of all wolves and foxes. And, of course, of ‘man’s best friend’ the domestic dog.

For further information, visit the Kenya Rangelands Wild Dog and Cheetah Project website

Kristin Davis – Why I Love Kenya

American actress Kristin Davis is perhaps best-known for her role as Charlotte York Goldenblatt in the American TV series Sex and the City for which she received a 2004 Emmy Award nomination. She also starred in the films Sex and the City 2008 and 2010.

A Global Ambassador for Oxfam, Kristin is also a ‘High Profile Supporter’ for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. She is also the 2010 winner of the Wyler Award, and a patron of the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. In this interview, Kristin tells us about her passion for conservation and why she loves Kenya.

Hi Kristin. When did you first visit Kenya? And what prompted the visit?

My first safari was in 2001. I’d always wanted to visit Kenya and, since all of my friends were busy working, I decided to just go alone. I spent time in the Chyulu Hills at ‘Campi Ya Kanzi’ where the view of Mount Kilimanjaro was magical: and where being able to go hiking in the cloud forests made me fall immediately in love with Kenya.

You’re a dedicated animal-lover with a special love of elephants. How did that come about?

I think my love of elephants began when I watched National Geographic specials as a child. I love the elephants’ social structure, their fascinating behaviour; and the contrast between their immense size and power and their incredible gentleness and goofiness.

Tell us why, in 2009, you started working with the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (SWT)?

I was at ‘Campi Ya Kanzi’, working with their conservation arm, The Maasai Wilderness Trust, when a Maasai elder told us that a baby elephant had been seen alone at dusk for two consecutive nights. Baby elephants can’t survive for any length of time without their mother’s milk so we knew something was seriously wrong. We called SWT for advice and support and then began a frantic hunt. It took us a day and a night to find her – she’d wandered deep into a lava flow – but with the help of the SWT team we rescued her. It was then that I realized that I needed to help raise awareness and funds for all the wonderful work done by SWT.

I was later honoured to be asked by Dame Daphne Sheldrick be a patron of the Trust. An honour I take very seriously indeed; and one that has prompted a lifetime’s commitment to ensuring that Daphne’s vision – of generations of elephants living freely and safely in the wild – becomes a reality.

What prompted you to make the 2015 ‘Gardeners of Eden’ documentary?

I wanted to share the beauty of the elephants so that the viewers might fall in love with them as I have done but my primary goal was to highlight the magnitude of the work of the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. Initially, I and my team made a short film called ‘WILD’ about the work of the Trust. Later, I was able to fund and produce the full-length documentary, ‘Gardeners of Eden’ in which we follow the anti-poaching teams and the veterinary teams who travel all over Kenya and treat any wild animal that has been injured. We also visit the Nairobi National Park SWT where the baby orphaned elephants are raised, as well as their rehabilitation centres in Tsavo.

Do you have a favourite place in Kenya?

It’s very hard to choose a favourite. I love the Chyulu Hills and Lamu - but my favourite place would have to be Tsavo National Park, because of its vastness and intense beauty.

What, for you, is the essence of what makes Kenya so lovable?

The wildlife is stunning, but the sheer diversity of the landscapes was unexpected. I’ve visited around 15 times and there’s still so much of the country I haven’t seen. I was also very impressed with the openness of the Kenyan people; and their warmth towards visitors.

For more information on the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, visit: www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org

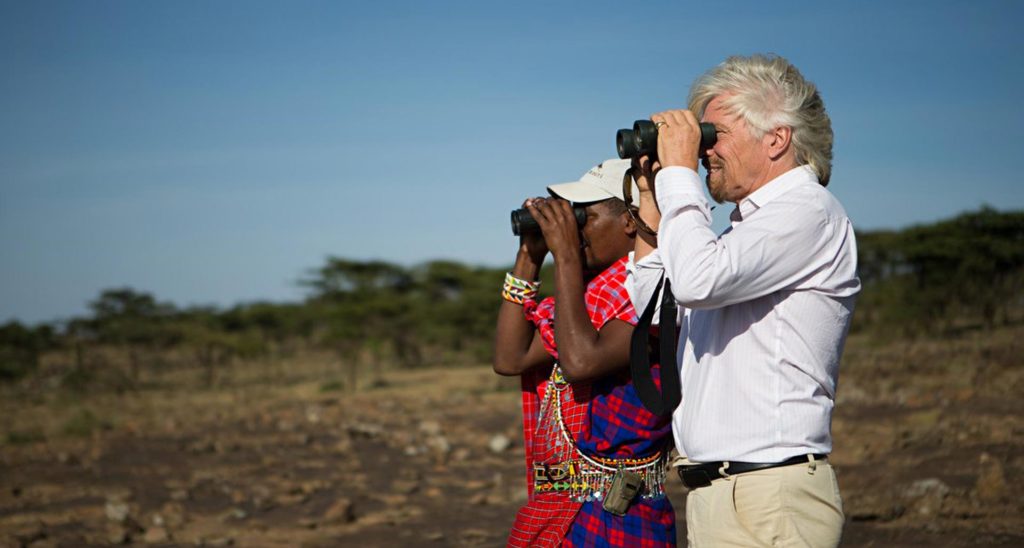

Richard Branson – Why I Love Kenya

In this article, world-famous entrepreneur Sir Richard Branson - English business magnate, investor, philanthropist and founder of the Virgin Group - tells us why he loves Kenya.

What were your first impressions of Kenya?

I found Kenya to be a beautiful country – full of wonderful people, wildlife and landscapes. It’s always such a pleasure to spend time here. Every visit is always a fantastic experience.

What is it that you love about Kenya?

There are so many things: the abundance of nature and the kindness of the people. Kenya offers a vast landscape of untouched beauty; it always gives one such a sense of peace. You can get so incredibly close to the wildlife in their natural environment. And there’s a unique sense of harmony about Kenya that you won’t find anywhere else on Earth.

What’s your favourite Kenyan experience?

I’ve had the pleasure of going on a number of safaris in Kenya but one of my favourite experiences is to take a group of local children on safari. It’s a chance for young people to learn about conservation and the wider world around them.

What prompted you to set up your camp in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy of the Masai Mara?

On one of my visits to Kenya, I was told by my great friend, Jake Grieves-Cook, that the annual migration of the wildebeest was in danger of being restricted by development. Jake suggested that, along with a number of other people, I invest in the area with a view to expanding the protected area for the benefit of both the local community and wildlife alike.

I followed his advice and we opened our 12-tent safari camp, Mahali Mzuri, on the Olare Motorogi Conservancy in 2013.

Why the Olare Motorogi Conservancy?

The abundance of animal life in the Olare Motorogi Conservancy is quite simply jaw-dropping. I’ve been lucky enough to enjoy the glory of the animal kingdom at its most dramatic just half a mile from the camp. Operating within a conservancy means that we are able to better control the number of vehicles and guests. This means the conservancy is not crowded, which is better for the guests and for the wildlife.

We’re also able to ensure that our guides adhere to a strict code of conduct and thus more effectively manage the impact of tourism on the environment. Working with the conservancy has also enabled us to create our own relationships and friendships with the local communities.

And what about the greater picture of Kenya on the world stage?

In recent years, the brutal poaching of Africa’s iconic wildlife has reached crisis point – driven by the ease with which poachers are able to operate in far too many of Africa’s national parks and wildlife reserves.

Kenya has, however, demonstrated good leadership in reducing the supply of ivory and rhino horn by burning 105 tons of confiscated ivory, which is equivalent to the tusks of roughly 8,000 elephants. She has also incinerated one ton of rhino horn. This sent an unambiguous message to poachers and traffickers alike to the effect that Kenya is no longer prepared to tolerate this bloody global trade. I think President Kenyatta said it best when he said ‘ivory is worthless unless it is on our elephants’.

Richard Branson and Mahali Mzuri photos © Virgin Limited Edition

Friends with benefits: taking a ride with an oxpecker

It’s a common sight: a small bird with a bright red beak is taking a ride on a zebra. It might be perched on its neck or riding between its ears. The zebra doesn’t seem to mind and the bird seems to be having fun. With good reason.

Bed and breakfast

The bird, which is an oxpecker, is not just hitching a lift; it’s having a free lunch. The main course might be ticks, the side-dishes might feature blood-sucking flies, fleas or lice. The starters will include earwax, saliva, eye mucous, sweat and blood.

The zebra is also providing accommodation – a safe place for an afternoon nap and a cosy spot in which to spend the night. Oxpeckers also like to mate while on the hoof and, when the young ones come, zebra fur makes the ideal nest-liner.

The oxpecker's early warning system

All of this suits the zebra just fine. Its average daily grooming time is drastically reduced. And, thanks to the services of a super-efficient parasite-killer, it can remain strong, healthy and attractive to potential mates. The oxpecker is also a professional when it comes to knowing exactly where to peck, which just happens to be behind the zebra’s ears – where it can’t reach – and where the parasites are at their thickest. Finally, should the zebra get into a fight, the oxpecker will clean the wound thus preventing both bacterial infection and blow-fly infestation. Fights, however, are discouraged by the oxpecker, which offers a world-class early-warning system. Perched high on the zebra’s neck, it surveys the bush for likely threats and, when it spots one, it shrieks, hisses and flies up into the air. It’s not subtle, but it works – especially with lions.

The oxpecker is built for the job

None of this happens by accident. The oxpecker, which comes in two varieties, the red-billed (Buphagus erythrorynchus) and the yellow-billed (Buphagus africanus) has been specially adapted for the job. Its bill is sharply pointed and can scissor its way through the zebra’s coat yanking out embedded parasites as it goes. It has short, jockey-like legs with sharp claws that enable it to remain in the saddle whatever the pace; and its short, stiff tail ensures perfect balance – even over jumps.

It is also relaxed when it comes to the choice of ride. Rhinos, kudus, giraffes, hippos and buffaloes are all acceptable. In fact recent research has revealed that groups of Tanzanian oxpeckers have taken to hanging upside down in the armpits of giraffe overnight.

Dark rumours

The relationship between the oxpecker and its various hosts has always been referred to as mutualism because it was thought that the benefits to bird and beast were mutual. Lately, however, dark rumours have begun to circulate and the oxpecker is being accused of vampirism. It shouldn’t come as a surprise. The oxpecker’s official name, Buphagus, means 'eater of ox'.

Want Inspiration in your Inbox?

Sign up for FREE to receive our monthly e-newsletter with features

and ideas to help you plan your Kenyan adventure

© 2025 Kenya Holidays