Born Free – an interview with Virginia McKenna

In this article, actress and activist Virginia McKenna OBE, who played Joy Adamson in the 1966 film, Born Free, tells us how her time spent in Kenya whilst filming Born Free changed her life.

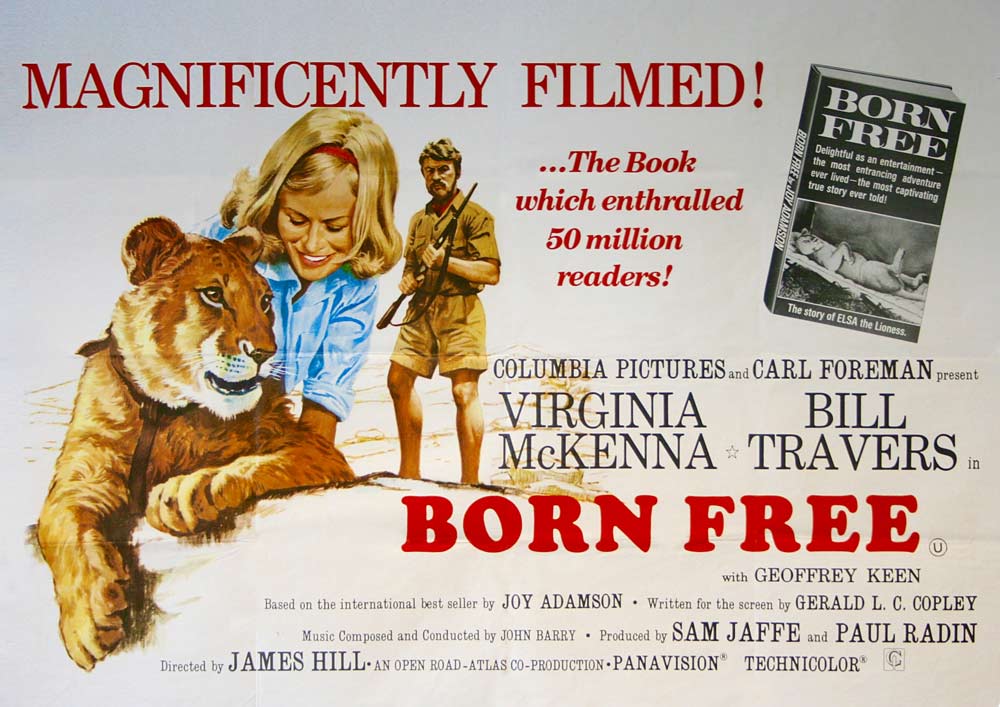

Virginia McKenna is a British stage and screen actress, author and wildlife campaigner, best known for such films as A Town Like Alice, Carve Her Name with Pride and Ring of Bright Water. But it was her role alongside her husband, Bill Travers, in the 1966 classic Born Free that was to change everything.

The film was based on the book, Born Free, by Joy Adamson, a worldwide best-seller read by 50 million people and translated into 21 languages. Born Free told the true-life tale of game warden, George Adamson, who adopted an orphaned lioness cub, Elsa, and Joy Adamson, who formed a unique relationship with her. Set in the Meru National Park, in northern Kenya, it was the most successful animal story of modern times.

The film also brought huge publicity to Kenya as millions all over the world saw, for the first time, the glory of her wilderness and wildlife. Finally, the story of Elsa the lion cub served as a catalyst for the cause of animal conservation and also earned Virginia the title, ‘the midwife of animal conservation’.

Born Free - first impressions of Kenya

You first came to Kenya in 1964 with your husband, Bill Travers, to begin work on the film, Born Free. Together you then spent 9 months living in the bush, living alongside lions and preparing for your roles. What were your first impressions of Kenya and how did those impressions change during your stay?

Where do I begin? It was a very long time ago – 55 years in fact - that Bill Travers and I sailed from London to Mombasa with our children to begin work on a film called Born Free, based on Joy Adamson’s famous book on her life with George Adamson. George was our ‘lion man’ and I have to say that without his quiet wisdom and sensitive guidance the film could never have been made.

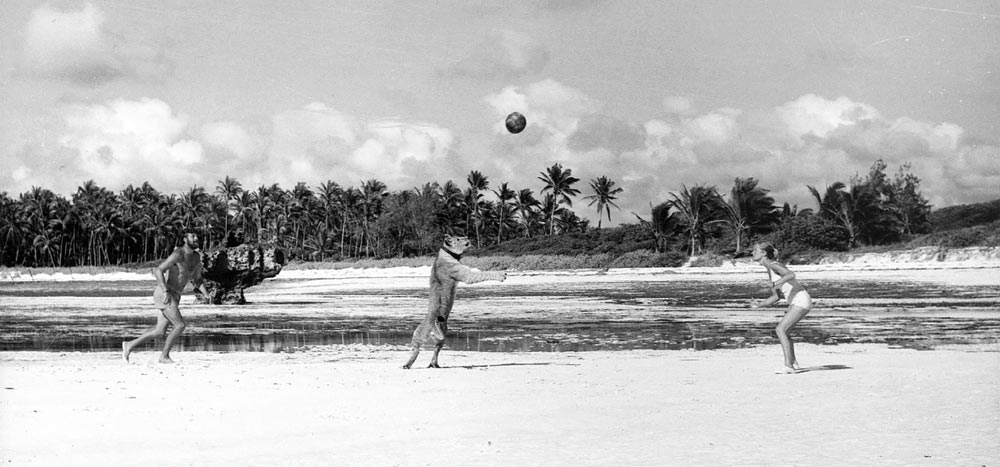

We had to work closely with six different lions after the two circus lions that had been selected to ‘play’ Elsa were deemed too unpredictable. This meant that we had to get to understand them - as individuals – and form relationships with every one of them. Our family home (and the base for the lions) was an old settlers’ house on a little river in the town of Naro Moru. My first memories of Kenya are of the great beauty of the land and the warmth and kindness of all the people we met. Also of the cloud-filled skies which, for some reason, never seem to obscure the sun. They’re memories that are echoed every time I return to Kenya.

Getting to know lions

You’ve been quoted as saying that making Born Free in Kenya had a tremendous impact on you and Bill. Could you tell us more?

It would have been impossible for anyone not to have been affected by the making of a film of Joy’s book, it was a love story. It was also the story of a relationship between a lioness and two extraordinary people and the unique and unpredictable journey they travelled together. For Bill and I, it was a leap into the unknown because we had to understand the different natures and traits of all the different lions who ‘played’ Elsa.

You’ve spoken about the fact that no matter how much you had read about lions, nothing had prepared you for the reality of meeting a lion.

Nothing can prepare you for the moment you actually meet a lion. How could it? Animals are all different – just like us – and you need, slowly but surely, to learn about their likes and dislikes; when they are bored or uninterested; whom they like or don’t like.

A lasting impact

What are your abiding memories of your time in the Kenyan wilderness and what, if anything, evokes your strongest memories of Kenya?

During the months of filming in Naro Moru we had no time to travel and experience ‘the wild’. But once filming was over we took our two eldest children, Will and Louise, on safari in Kenya and Tanzania. It was an experience never to be forgotten: not only of seeing such iconic creatures as elephant, lion, rhino, cheetah, giraffe, but also of encountering the birds, herbivores and the miraculous dung beetle, which will always remain one of my very special creatures.

In your journals, you wrote about how leaving Africa was ‘agony’, as was saying goodbye to the many ‘Elsas’ who starred in the film. Can you elaborate?

We worked with over 20 lions and had close and extraordinary relationships with a number of them. So you can imagine our horror and disbelief when, at the end of filming, we were told that they had been sold to a series of zoos and safari parks. Joy and George shared our horror, but it was too late – the deals had been done.

We did, however, manage to save two lions called Boy and Girl. Also a large male called Ugas who joined George’s little pride of lions. The other lions were not so lucky: our much-loved Mara and Little Elsa went to Whipsnade Zoo in England while fun-loving Henrietta was returned to Entebbe Zoo in Uganda.

Our sense of having betrayed these creatures ran very deep. So deeply, that Bill decided to make a documentary about our visit to Mara and Little Elsa at Whipsnade Zoo. It was an experience I will never forget. It was also the inspiration for the many documentaries Bill would make over the coming years and which opened up a new path in life for him.

As for George, a friend for life, he set up a simple camp in Meru where he cared for the three lions we had saved. You can still see the site today. It lies just below the current lodge, Elsa’s Kopje, a beautiful place where I stay every time I visit Meru. You can also still see the rusting remains of George’s various vehicles as they lie in the bush - poignant reminders of the path that would ultimately lead to his tragic death.

Born Free and Living Free

You’ve said that every creature, human and non-human, deserves to be born free and stay free. Could you tell us how you’ve translated this belief into the establishment of the Born Free Foundation?

I have always found it challenging to accept that wild animals can be kept in captivity; that they can be removed from their mothers and sent to zoos in distant lands, that they can be subjected to living in cages or enclosures; and that they can be denied companions of their own kind and required to mate according to the dictates of man.

Worse still that they should be sold to circuses, which are really travelling menageries where they are trained to perform tricks such as standing on tubs, jumping through hoops or riding horses with loud music blaring around them. Surely such spectacles belong to history. I also question how we can watch wildlife documentaries - in wonderment - and yet still approve of wild animals being kept in captivity?

The spirit of Elsa

Born Free was released in 1966, would you say that the understanding of wild animals – their natures, needs and desires – has improved dramatically since then?

I think that a growing number of people do think very differently now – especially when they hear about the rescues that we, and other groups, have carried out; such as ensuring that wild animals be removed from concrete cages, circus trailers or private ‘ownership.’ But the horror stories still continue. And many of them are not only condoned but also compounded by the extraordinary indifference displayed by those in positions of authority.

It is also true that fewer circuses use wild animals in the United Kingdom, though the same does not apply elsewhere in the world. There is also the fact that as the human population increases so the availability of land for the wildlife decreases, and this leads to conflict between man and wildlife and between the wildlife itself.

Perhaps it’s time for the spirit of Elsa to be reborn; time for people to learn to respect and treasure our wildlife and wildernesses; and to conserve the natural world, whose beauty and seasonal change so enriches our souls. I may be an eternal optimist, but I am always encouraged by my visits to Kenya where I rejoice in the beauty of the land and its creatures.

I’m also encouraged by my meetings with the school children who already care so deeply about wildlife – despite the fact that many of them have only encountered it in the form of pictures. I recall one particular young boy, who asked, ‘Please Miss, why do men kill lions?’

The Born Free Foundation

Born Free changed many lives, but especially those of Virginia and Bill who devoted their lives to campaigning for animal rights and to the establishment of the Born Free Foundation. Today, the Born Free Foundation has 100,000 supporters worldwide and spends more than £2 million every year fighting animal exploitation, conserving endangered species, and re-homing animals from run down zoos to Born Free sponsored sanctuaries all over the world.

For further information visit: www.bornfree.org.uk

Kenya’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites

There are some places on earth that are so unique and culturally significant that the nations of the world have come together to protect them for generations to come. These places are the UNESCO World Heritage Sites, listed and protected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Proudly protecting seven of mankind’s greatest treasures, Kenya's World Heritage sites are:

1. The lakes of the Great Rift Valley

Literally the most prominent of our sites, since it can be seen from the moon, is the lake system of the Great Rift Valley. Strung out like jewels along the floor of this huge volcanic rift, Lakes Nakuru, Elementaita and Bogoria not only protect one of the world’s greatest diversity of bird species but they are also home to some four million Lesser Flamingoes, which migrate between their shimmering grey-blue waters, hot springs and spectacular escarpments.

2. Mount Kenya National Park

Equally prominent on the geographical stage are the icy spires of Mount Kenya, Africa’s second highest mountain. Straddling the equator, striated by glaciers, cloaked in forests and climbed by thousands of tourists every year, the vast bulk of this mountain is all that remains of a volcano that erupted three million years ago. A migrational route for elephants since the dawn of time, Mount Kenya is not only a conservation stronghold but also the finest example of an Afro-alpine landscape.

3. The sacred forests of the Mijikenda

Down amid the dense forests that cloak the Indian Ocean coast lie the sacred forests and fortified villages - known as kayas - of the Mijikenda people. It was to the safety of these forests that the so-called ‘Nine Tribes’ fled during their migration from Somalia in the 16th century; and it is in these shaded groves that their ancestors are still believed to live.

4. Lamu Old Town

To the far north of the lovely Kenyan coast stands the 14th century town of Lamu, the world’s best-preserved example of a Swahili settlement. A place of winding lanes, wandering donkeys and soaring minarets, Lamu is the very embodiment of the coastal character of East Africa.

5. Fort Jesus, Mombasa

Heading south, and standing at the heart of Mombasa’s Old Town, is the magnificent Fort Jesus. Built in the 16th century by the conquering Portuguese to protect the port of Mombasa, this black-streaked bastion has withstood centuries of siege warfare; and its rusted canons still glower out to sea.

6. The Lake Turkana National Parks

Shimmering like a mirage in the harshly beautiful desert landscape of northern Kenya lie the blue-green waters of Lake Turkana. On its shores is one of the world’s greatest treasures, Sibiloi National Park, home to the three-million-year-old Koobi Fora paleontological site. First discovered by Dr Richard Leakey and his team in 1972, Sibiloi shelters the remains of our earliest ancestors, Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Homo erectus and Homo sapiens. It’s known simply as the ‘Cradle of Mankind’.

7. Thimlich Ohinga Archaeological Site

Finally, the newest member of Kenya's exclusive UNESCO club is the Thimlich Ohinga archaeological site. Situated north-west of the town of Migori, in the Lake Victoria region, this dry-stone walled settlement was probably built in the 16th century. Thimlich Ohinga is the largest and best preserved of these traditional enclosures and is an exceptional example of the tradition of massive dry-stone walled enclosures, typical of the first pastoral communities in the Lake Victoria Basin.

And, as if the guardianship of this priceless array of global gems were not enough, Kenya currently has some 17 sites on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites 'tentative list'. These include the Aberdare Mountains, the Mfangano-Rusinga Islands, the ancient Swahili town of Gedi, Lake Naivasha, Lake Nakuru National Park and Mombasa Old Town.

So, whether it’s geographical grandeur, ecological brilliance or cultural marvels that you’d like to experience – we’ve got them all. Come to Kenya…and explore the inheritance of our Earth.

For more information on Kenya's World Heritage Sites: whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/ke

Why are Flamingos pink?

Well, actually, they’re not.

Strange but true: flamingos are born grey and their feathers only turn pink as they eat their preferred diet of the blue-green algae, Spirulina, which contains a natural pink dye called canthaxanthin. Consequently, flamingos kept in zoos turn from pink to grey, unless they have synthetic canthaxanthin added to their diets.

The most fabulous bird spectacle on earth

Spirulina has a lot to answer for in the life of the flamingo: a periodic low Spirulina count in the waters of their most famous home on Lake Nakuru causes them to migrate north and south to Kenya’s other lakes. If there’s a high Spirulina count, however, then as many as 1.5 million birds might arrive to create what famous ornithologist Roger Tory Peterson called, ‘the most fabulous bird spectacle on earth’.

The spectacle comes, however, at a price because an average population of 300,000 flamingos suck around 180 tonnes of Spirulina out of the lake every day. That’s a lot of algae. And nor is it always available. Sometimes, after a long dry period, the level of the water in the lake will reduce and its alkalinity will increase. This is bad news for the Spirulina, which cannot tolerate too high an alkaline content. Consequently they shrivel up and die.

This leaves the flamingos with a conundrum: they can deviate from their diet, depart for another lake, or die. It’s a tough choice and, though the flamingos try to survive on an alternative algae known as Clamydomonas, it’s considerably smaller than Spirulina and slips through the filtering system of their beaks. So, faced with starvation, they have only one choice – to migrate.

In search of Spirulina

Migrating flamingos make for one of nature’s most glorious spectacles. Rising from the lake in choreographed flights of coral pink, they head off in V formation, streaking the blue skies pink, and filling the air with the sound of their honking. Where do they go? Any large expanse of water might attract them, but not before they’ve checked it out for Spirulina. And if the menu isn’t up to scratch, they’ll move on. Sometimes south, sometimes as far north as up to Lake Turkana, even to Ethiopia and Botswana.

The lesser flamingo is one of the world’s six flamingo species, but when it comes to eating Spirulina, it’s a master of the art. Custom-built for the job, it has long legs that allow it to wade and feed in water nearly a meter deep, while its long neck allows it to reach down into the water where it feeds with its head upside down.

Flamingos harvest their algae by ‘grazing’ along the top of the water, skimming only a few centimetres of it into their elegantly curved bills. Inside the bill is a complex filtration system. The upper mandible is triangular and fits tightly into the lower bill when closed, and the inner surfaces of both are covered with fine hair arranged in rows of about four to the centimetre. The thick, fleshy tongue fits neatly into a tubular groove in the lower mandible where it moves back and forth like a piston. As the tongue retracts, water is sucked in over the filter hairs; as it extends the water is forced out causing the algae to be caught in the fine filament hairs of the mandibles. Consequently, if you watch a flamingo feeding, you will notice a pulsing ring of water coming rapidly out of its beak.

Did you know?

It’s not only flamingos that thrive on Spirulina – it is also highly beneficial to humans - being rich in protein and a good source of antioxidants, B-vitamins, iron and calcium. Indeed so nutrient-packed is Spirulina that it has been dubbed ‘the most nutrient-dense food on the planet’. The good news is, however, that it doesn’t turn humans pink.

Flamingo Facts

Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus)

Identification: 56 in / 142 cm. Plumage white with a pink wash, wing-coverts and auxillaries bright coral-red; flight feathers black, bill pink with black tip – a much larger and paler bird than the lesser flamingo, easily recognised by its pink bill and ‘S’-shaped neck.

Lesser Flamingo (Pheonicopterus minor)

Identification: 40 in / 101 cm. Plumage deep pink, much darker and brighter than the greater flamingo; bill dark carmine-red with black tip.

A Mother’s Love

Elephants are expressive creatures. They display joy, anger, grief, compassion and love. But a mother’s love for her calf is the strongest emotion of all.

Elephant mothers carry their babies for almost two years before giving birth. Mother and child remain in constant touch, the calf never straying more than a trunk’s length from its mother, while she gently steers it by grasping its tail with her trunk.

Elephant mothers know best

The mother carries her calf over obstacles, rescues it from mishaps, and uses her own body to protect it from attack: even from the hot sun. She bathes it using her trunk, both to spray water over it and to gently scrub it clean. Protector and nurturer, the mother is also the calf’s teacher. From her it will learn where to find water, what to eat, and how to avoid its only predator – man. It’s a lot to learn for a small elephant, which for the first six years of its life will only taste solid food in its mother’s mouth, and receive sustenance only from her milk. And to ensure her calf gets exactly the right nutrients, an elephant mother’s milk changes four times during the weaning process.

Family ties

Elephants have the longest childhoods of any creature on earth other than man and, like us, they stay in family groups until they reach puberty (10-15 years). However while the females may stay with the matriarchal herd for life, the young bulls must leave as soon as they reach puberty. Capable of mating at the age of ten, they will not be socially mature until they have reached the age of thirty, at which time they will have attained the size and the experience to compete against the other bulls for the females when they are on heat.

Elephant dating

Elephants herds are matriarchal. The oldest female elephant plays a key role in controlling the social network of the group and in ensuring the survival of the family. And when it comes to choosing a mate, the female always has the last word. Careful study of elephant behavior in Amboseli National Park has revealed that the female elephant knows exactly what she wants in a male. Those she fancies, she entices by brushing gently up against them, coyly hesitating to one side, or simply striding up and saying hello. Those she doesn’t favour, she simply ignores, tosses her head at – or runs away from.

Sound familiar? Well so it should.

The Maasai – the keepers of God’s cattle

It’s one of Kenya’s most iconic images. The Maasai warrior, spear in hand, scarlet shuka cloak thrown over his shoulder, one leg raised to rest on the other and his gaze turned to the far horizon. Certainly the most visually striking of the many colourful tribes of Kenya, the Nilo-Hamitic Maasai are a nomadic people whose way of life has remained unchanged for centuries and is still dictated by the constant quest for water and grazing land for their cattle.

Maasai and their cattle

Called ‘Maasai’ after their language, ‘Maa’, the Maasai are renowned for their bravery. They are also distinguished by their complex character, good manners, impressive presence and almost mystical love of their cattle. ‘I hope your cattle are well’ is still the most common form of Maasai greeting, whilst milk and blood remains the traditional Maasai diet. Cowhides provide basic necessities such as mattresses, live cattle establish marriage bonds, and a complex system of cattle-fines maintains social harmony.

Adapting to change

Thought to have migrated to Kenya from the lower valleys of the Nile, the Maasai encountered a troubled history in their adopted home. Firstly their people were decimated by famine and disease; secondly they lost many of their cattle to the scourge of rinderpest; thirdly their development was affected by the arrival of the European explorers; and, finally, they lost much of their land to the British settlers. Nor did their dispossession end there. In recent years they have also had to endure the steady shrinkage of their ancestral lands thanks to urban expansion and the establishment of Kenya's National Parks and Reserves.

Undeterred, however, the Maasai have risen to the challenge. Many have entered into cooperative ventures with the tourism industry and created conservancies on their land. And, rather than killing lions, as was the custom of the young warriors of the past, the morans of today are actively engaged in protecting them. Some things, however, never change – such as the Maasai love of their cattle. No matter how large the herd, each cow will have a name and a lineage. And only in the harshest of circumstances will a Maasai part with a single animal.

The tale of Maasinta

So why do the Maasai love their cattle so dearly? Perhaps the best explanation is given by the Maasai themselves in the following folk tale.

In the beginning, the Maasai did not have any cattle. Then one day God called to Maasinta, who was the first Maasai, and said to him, ‘I want you to make a large enclosure, and when you have done so, come back and inform me’. Maasinta went and did as he was instructed. Then, God said, ‘tomorrow, very early in the morning, go and stand in the enclosure and I will give you something called cattle. But keep very silent no matter what you might see or hear.’

Very early in the morning, Maasinta went to the enclosure and waited.

Suddenly there was a great clap of thunder and a leather thong descended from heaven. Down it descended hundreds of cattle in all the shades of brown and black - some with great horns, others with velvet dewlaps. Meanwhile the earth shook so violently that Maasinta’s house nearly fell over and he was gripped with tremendous fear, but he did not make a sound.

It was at this moment that Dorobo, who shared the house with Maasinta, woke from his sleep and went outside. There, seeing the cattle descending down the leather thong, he let out a great shriek.

Immediately God withdrew the thong into heaven and, thinking that it was Maasinta who had shrieked, He said to him, ‘what’s the matter? Are these cattle not enough for you? If that is the case, I will never send any more – so you had better love these cattle in the same way that I love you.’

And so, according to legend, that is why the Maasai love their cattle so much.

This folk tale has been adapted from Naomi Kipury’s Oral Literature of the Maasai and Kenyan Oral Narratives by K. Adagala and W. Kabira.

Want Inspiration in your Inbox?

Sign up for FREE to receive our monthly e-newsletter with features

and ideas to help you plan your Kenyan adventure

© 2024 Kenya Holidays