Gedi ruins

Originally occupied in the late 11th or early 12th century, the ruins of the Swahili city of Gedi are located just 7 km north of Watamu. Ideal for an early morning or late afternoon visit, when you fancy a break from the beach, Gedi is deliciously cool and offers a fascinating insight into local history and ancient architecture.

Gedi - a flourishing city

Meaning ‘precious’ in the language of the local Galla people, Gedi is thought to have flourished in the mid-15th century. It hosted sultan’s palaces, sunken gardens, a fabulous selection of grand merchant’s houses, a large Friday mosque and some exquisite examples of Islamic pillar tombs. Many of the inhabitants - some 2,500 - were wealthy and powerful, benefiting from extensive trade with Arabia and China.

Then, in the 17th century, it was abandoned, some think quite suddenly. Theories abound as to why this happened: one being the presence of the Portuguese; another being that the residents fled in the face of an imminent invasion by the Galla, who were known to be cannibals.

Excavations of the ruins during the 1940-50s revealed an extensive array of domestic, religious and commercial structures. These included a palace with sunken courts, fortified walls and a deep well. Finds included glass and shell beads, gold and silver jewellery, coins, porcelain and local pottery.

Also uncovered was the earliest evidence for occupation at Gedi - a grave marker that has been dated to between 1041 to 1278. While the adoption of Islam by the inhabitants in the twelfth century is evidenced by the presence of three mosques in the northern area the city.

A sacred site

Today, the picturesque ruins are spread over 45 acres, dotted with ancient baobab trees and surrounded in dense coastal forest rich in birdlife and wildlife. The local Giriama, one of the Mijikenda tribes, view the site as a sacred and spiritual place. Many believe Gedi to be haunted by a strange ‘beast’ which stalks visitors as dusk falls.

The Historic Town of Gedi is also on the UNESCO World Heritage Site 'tentative' list.

The Gedi experience

A tour of the ruins - some 1.5km in length - will take around an hour. There are also some lovely walks away from the ruins through the thick forest where you might be fortunate enough to spot the endangered golden-rumped elephant shrew. For a bird's eye view, the Arabuko-Sokoke Schools and Ecotourism Scheme has built an observation platform in a baobab tree overlooking the site.

Getting there: Just 7 km from Watamu and 15 km from Malindi, Gedi ruins is easily accessed by taxi or bus. The ruins are open 7am-7pm (a small entry fee is payable).

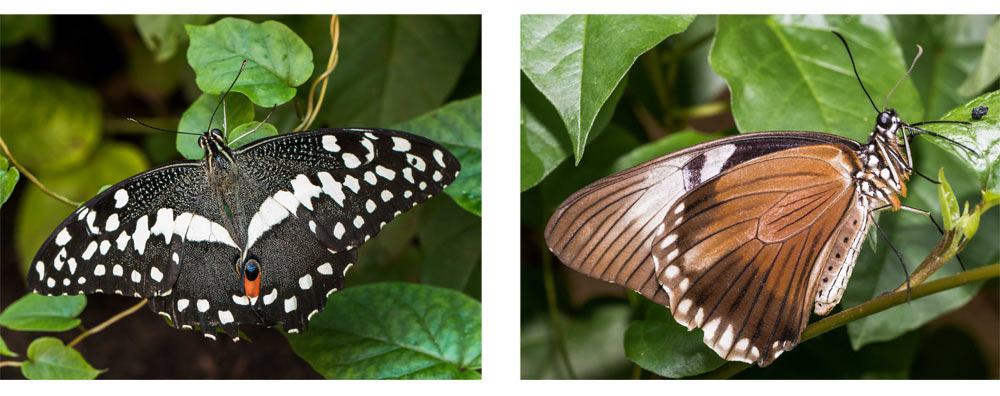

Kipepeo Butterfly Project

Immediately adjacent to Gedi is the fascinating Kipepeo Butterfly Project. Kipepeo means butterfly in Swahili and this community-based eco-farm offers an enchanting butterfly display house, with over 250 species. There is also an education centre showcasing the range of butterfly products.

Local farmers are able to earn a living from the nearby Arabuko-Sokoke forest by rearing butterfly and moth pupae for export to live exhibits and butterfly houses in Europe and America. The project also exports honey and silk cloth produced by the local community.

For further information: Kipepeo.org

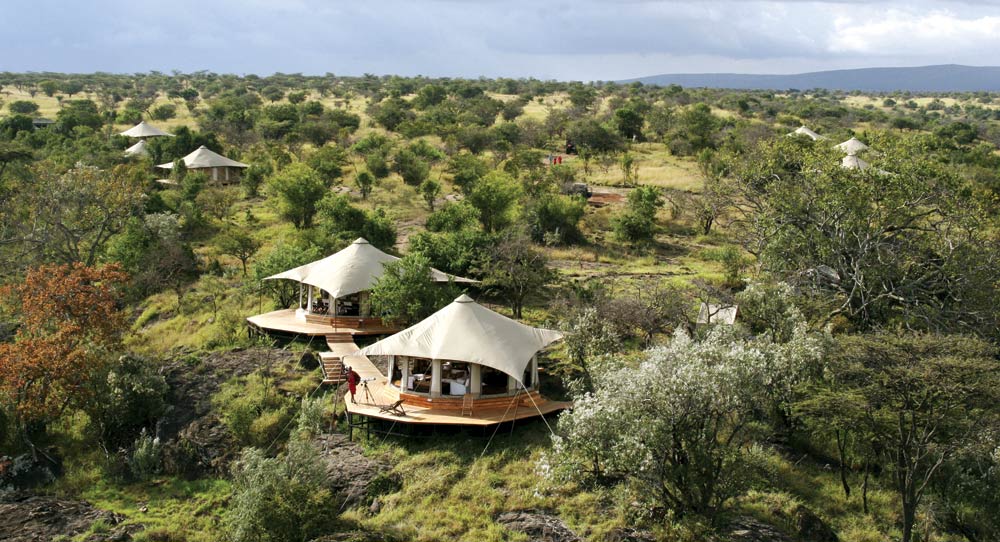

Kenya’s conservancies, the new safari experience

Ask any motorcyclist why they prefer a bike to a car and they’ll probably tell you that they prefer to be IN the moment rather than looking at life through a window. It’s the same with the safari experience and that's where Kenya's conservancies come in.

The majority of visitors explore Kenya’s globally-renowned national parks from the comfort and safety of a safari vehicle. Increasingly, however, there are those who want to leave the safari vehicle behind and get their boots on the ground: to walk or ride across the wilderness.

Conservancies are the new frontier of Kenyan tourism.

© Hemingways Collection

So, what’s the difference between a conservancy and a national park or reserve?

The quick answer is that, in general, the national parks and reserves are longer-established, some dating back to the 1940s when they were created specifically to protect Kenya’s wildlife and wilderness. They’re also more ‘high-profile’ including such well-known destinations as the Masai Mara, Amboseli, Samburu and Tsavo, amongst their 56-strong ranks. Nationally owned, they are administered by the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), permit no human activity, such as herding, and are generally much more restrictive in the range of activities permitted.

Kenya's conservancies are a different species. They’re younger, the first one having been established in the 1980s, they’re community-owned and run, and they’re dynamic.

Less restrictions, more experiences

As to restrictions – conservancies only limit the number of camps, lodges and vehicles allowed on to their land. This lowers the environmental and ecological impact of tourism and improves the visitor experience. They don’t however restrict the activities on offer. This means that visitors can enjoy unique safari experiences such as walking safaris, horse-riding safaris, camel safaris or night game-drives (all of which are not allowed by KWS run parks).

Ecologically sound

Typically, the conservancies occupy land either previously held privately or only relatively recently reverted to wilderness. Sometimes the border between a national park and a conservancy might be nothing more than a line of white stones. Consequently, the scenery is the same and the wildlife wander back and forth at will. However the wildlife densities in conservancies are higher, while the numbers of tourists viewing the wildlife are lower. Crucial too, is the fact that the extension of sheltered wilderness has allowed a network of wildlife corridors to be extended across the country. And this means that many animals, such as elephants, can follow the ancient migration routes that they have trodden since the dawn of time.

A powerful partnership between the communities and the tourism industry

Most importantly of all, conservancies are managed according to a model that protects the delicate ecosystem and benefits the landowners themselves.

When, for instance, a group of Maasai people decide to turn their ancestral lands into a conservancy they not only derive an income from visitor fees and accommodation but they can also still use the land to graze their herds. The income can finance schools, health centres and wells – but the land is still theirs for posterity.

Kenya's conservancies also promote new livelihoods such as bee-keeping or handicrafts, which provide an income for the women of the community. This empowerment has a positive impact on communities and helps prevent negative practices, such as the incidence of child brides and the tendency of impoverished communities to deny education to girls.

Conservancies also use their income to provide training for the growing number of young males unable to find work and to provide the technical skills that ensures the land is well maintained and improved.

Kenya's conservancies: sanctuary for endangered species

Crucially, the conservancies provide sanctuary for those endangered species such as rhinos that are threatened by poachers and which also can no longer remain in the national parks due to the fact that their numbers have exceeded the ability of the biosphere to support them. And they reduce the incidence of human-versus wildlife conflict by teaching people how to construct predator-proof enclosures and elephant-proof fences.

In the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy for example, the rhino population has grown from an initial 15 rhinos to 169 rhinos today.

The conservancies of the Masai Mara

The Masai Mara offers the perfect case study. It is surrounded by 15 conservancies that protect 450,000 acres of hitherto unprotected land upon which is enacted the world-famous annual migration of the wildebeest. In the greater Trans Mara, the lion population has doubled over the last decade. And 3,000 households have earned more than $4 million annually from tourism.

And the tourist still has the best of both worlds: access to the world-class vistas and world-famous lodges of the National Reserve and the chance to walk the wilderness, ride alongside zebra, or observe a lion pride in solitary splendour. A wilderness win:win.

The conservancy equation

Kenya has lost nearly 70% of its wildlife during the past 30 years.

65% of Kenya’s wildlife live in community and private lands

Kenya has 160 conservancies (4 of which are marine) covering 6.36m hectares, which is 11% of Kenya’s land mass

90% of all endangered hirolas and Grevy’s zebra reside on conservancies, 72% of southern white rhinos and 45% of black rhinos. Incidences of reported human versus wildlife conflict between 2011 and 2015 increased by 86% nationally, but on the private conservancies it decreased by 72%.

For more information, visit: https://kwcakenya.com/

Dinner on a Tamarind dhow

A favourite with visitors to Mombasa and the coast, the Tamarind Dhow experience promises a five-course dinner on the deck of an authentic ocean-going dhow.

The oldest ships to remain under sail, the Indian Ocean’s dhows are a living museum to the ancient art of shipbuilding. The two Tamarind dhows, both of which traded between Mombasa and Saudi Arabia before being transformed into restaurants, are more properly known as Jahazis. They can be up to 50 tons in weight, 60 feet in length, with a long keel, square stern, forward-raked mast and a lateen (triangular) rig. Run by the Tamarind Group, who also own Nairobi’s famous Carnivore and Tamarind seafood restaurants, they sail from the jetty below the Mombasa Tamarind Restaurant overlooking Kilindini Harbour.

The Tamarind dhows Nawalikher and Babulkher are broad in the beam and full-bellied, with feature red velvet seats and white damask tablecloths. On the raised poop deck the captain presides and steers the great ship with a lazy flick to the staves of the huge wooden wheel.

Underneath the poop deck is a stage where a live band performs. And beneath the main mast are the glowing charcoals upon which dinner will be broiled. First comes a traditional ‘Dawa’ cocktail (vodka, lemon and honey), followed by a delicately flavoured soup. The main course might be fresh ginger prawns, a seafood selection or a grilled steak. And there's always a delicious choice of homemade puddings or fruit salad. The service is cheery, the atmosphere party, and the passengers an engaging mix of tourists and local families.

As traditional Arab coffee is served, the dhow makes a stately turn and motors sedately down the creek to arrive back at her moorings.

Tamarind dhow facts

Nawalilkher can seat 70 for dinner, leaving plenty of room for dancing on the night cruises. It can host cocktail parties for up to 100 people. It is also available for private hire.

Babulkher has a capacity of 55 guests for dinner and 70 guests for cocktails and is also available for private charter.

The lunchtime cruise departs from the Tamarind jetty at 1.00 pm and cruises gently up the Tudor creek to moor for lunch. The dhow returns to the jetty at 3.00 pm.

The evening cruise departs at 6.30 pm and the dhow sails southwards towards Fort Jesus. The dhow returns to the jetty at 10.30 pm.

To book, visit the Tamarind website.

All images © Tamarind Group.

Reteti Elephant Sanctuary

‘My human family is at home,’ says the young Samburu mother, ‘but I’m also mother to another set of babies.’ She points to a herd of around a dozen young elephants. Some are tiny tots and others stand as high as a man. A softly probing elephant trunk wraps itself around Josephine’s waist. She laughs as it explores deep into her pocket in search of treats. I’m in northern Kenya spending a day at the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary. And it’s not far off feeding time.

Anticipation mounts as the baby elephants career across the landscape, causing plumes of red dust to dance off into the bush. Now they’re chasing each other around a clump of trees – trunk to tail. There’s a splishing and splashing of water as they career through a muddy pool. They’re like any other children on earth – only larger.

Kenya's Northern Frontier

A place of sun-baked earth, rust-red dust, scrubby thorn and vast, theatrical skies, Northern Kenya lies far from the well-beaten tourist track. Its empty vastness rolls away, unchecked, all the way to Lake Turkana and it glances only fleetingly off the boundaries of the much more famous Samburu National Reserve. Not many visitors make it out here. At first glance, you could be forgiven for wondering why they come at all. The landscape appears inhospitable in the extreme. But for all this, Northern Kenya shelters a rare and magnificent wildlife cast.

Here, in this desiccated region, roams the rare reticulated giraffe and the critically endangered Grevy’s zebra. Here too patrols the rare blue-shanked Somali ostrich and the bizarrely long-necked gerenuk. This is also an increasingly popular hideaway for the threatened wild dog or ‘painted wolf’. And finally, the wild reaches of the land - known romantically as ‘the Northern Frontier District’ - provides sanctuary for one of the largest and most nomadic elephant populations in Kenya.

Elephants on the move

Due to the paucity of food and water, the elephants are always on the move. Their ceaseless wanderings take them from the chilly moorlands bordering Mount Kenya to the volcanic uplands of Marsabit. Along the way, they pass through parchment-dry acacia scrub and bone-dry river gullies before eventually reaching the dripping-wet, mist-wreathed forests of the mountain ranges. It’s a journey of hundreds of kilometres, and it forces them to encounter hazards ranging from humans to fences, and from wells to roads. Inevitably there are mishaps along the way, and numerous baby elephants are left orphaned every year. These are the denizens of Reteti Elephant Sanctuary.

It was in 2016 that Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, the first of its kind to be entirely community owned and managed, was established in the forested foothills of the little-known Matthew’s Range of mountains, which lie a couple of hours’ drive north of the Samburu National Reserve. Here, the formation of numerous community conservancies has done much to reduce both the poaching of wildlife and the incidence of human-versus-wildlife conflict. Indeed, since 2012 an impressive 53% fall has been registered in the number of elephants killed by poachers in northern Kenya. This is a triumph of conservation.

Josephine's babies

Eying her surrogate babies at play, Josephine tells me that it was the sad plight of the orphans that initially spurred her community into action. ‘Many babies came to us as a result of accidents,’ she says. ‘Quite a few fall down wells and have to be rescued. We bring them here to recover though our aim is to return them to the wild if we can.’ As she speaks, her babies are becoming increasingly boisterous in their demands for attention. ‘They’re getting excited,’ she says, ‘they know it’s nearly time for their afternoon milk.’

At the mention of the word ‘milk’ five or six men in military fatigues march into our midst. Each burly man carries an over-sized baby’s milk bottle with a large pink teat. It’s a surreal scene. The bright eyes of the baby elephants lock on to the bottles and sudden pandemonium breaks out. They rush en masse towards their feeders. Amid the gulping and sucking that ensues, two Samburu warriors arrive to watch. They’re gorgeous in extravagant feathered headdresses and festooned in multiple strings of rainbow-coloured beads. At first their faces remain inscrutable. Then they register mild curiosity. Finally they split into broad grins.

And yet, just a few short years ago, such warriors would have regarded even these enchanting baby elephants as potential threats. And, rather than smiling upon them, they might have been more inclined to drive them away: or kill them. Happily, times have changed. Now the northern communities have banded together in defence of the elephants that share their impossibly arid environment. And the future looks bright for community and elephants alike.

Need to know

Visits to the Sanctuary can be easily arranged by most of the camps and lodges in the vicinity.

The author flew in to Nairobi from Europe with Kenyan flag-carrier, Kenya Airways and the sanctuary can be reached via airstrips at Kalama or Samburu, both of which are served by Airkenya.

For further information: www.retetielephants.org

A visit to Mzima Springs

Travel writer and author, Jane Barsby, takes a dive into Mzima Springs, one of Tsavo West’s greatest tourist attractions.

Mzima Springs is a world unto itself. Here in this magical bubble of an oasis, the air is filled with birdsong and the water bursts out of the ground literally gurgling with laughter. And so it might. It has been trapped underground for 25 years or more and now, finally freed from the underground chasms where it has achieved diamond-clarity, it will flash briefly through the pools of Mzima Springs before disappearing again.

The underwater hippo-viewing chamber

We’re in an underwater viewing-tank sunk below the waters of Mzima Springs in Tsavo West National Park. The water, melt-water from the snows of Kilimanjaro, has flowed here through many kilometers of underground tunnels. The tank smells damp and subterranean. Our voices echo hollowly. The tank, or so the brass plate bolted to the wall informs us, was installed in 1969. The other brass plate reads: Do not stick fingers into water. Crocodiles abound.

Tiny square windows are set into the structure’s cylindrical sides. Through them we can see hundreds of blue-grey fishes. The fish, known as barbels, are a type of fresh-water carp. They’ve got miniature shark-fins and translucent fangs and they’re all swimming around and around and around the diving bell in an anticlockwise direction. It’s dizzying to watch.

The water beyond the squared windows is crystal clear. In the shimmering distance we can just make out a set of short stubby legs. They’re paddling their way through the water with a vaguely pig-like submarine trot; and they’re attached to a vast chocolate-brown body with a raspberry-pink belly. It’s a hippopotamus. And it’s heading our way.

For a second or two the door of the chamber emits an eerie sci-fi glow as multiple cameras flash. Then the cavalcade emerges and snakes on down the path to the lower pool.

The hippos of the lower pool

Here, some thirty hippos are wallowing against a Hollywood-perfect backdrop of trailing lianas and dense green jungle. There’s a general snorting and blowing as they rise briefly to the surface to survey their audience. And a resounding chortle as they sink once more beneath the surface.

From the murky shallows a long, brown snout protrudes. Slowly, silently, hardly breaking the surface of the water, it drifts out into the wider reaches of the hippo pool. It looks like a log. But it has teeth. And so do all the other logs.

Crocodiles abound…

Mzima Springs Factfile

The word 'Mzima' means 'alive' in Kiswahili.

The transparent water of the three Mzima pools is filtered by the porous lava of the Chyulu Hills. Through a pipeline installed in 1966, Mzima Springs is also the source of most of Mombasa's drinking water.

There are two nature trails which lead to the underwater viewing chamber lined with date and raffia palms. As well as hippos and crocodiles, expect to see vervet and Sykes' monkeys and an incredible variety of birds.

Want Inspiration in your Inbox?

Sign up for FREE to receive our monthly e-newsletter with features

and ideas to help you plan your Kenyan adventure

© 2025 Kenya Holidays