The Bomas of Kenya

The Bomas of Kenya offers an unprecedented insight into the authentic cultural heritage of Kenya. Something of a time machine, it has captured an ethnic snapshot of a fascinating range of cultures, many of which are fast disappearing under the onslaught of the technological age. The Bomas of Kenya is a highly popular day trip when in Nairobi... so we went to check it out.

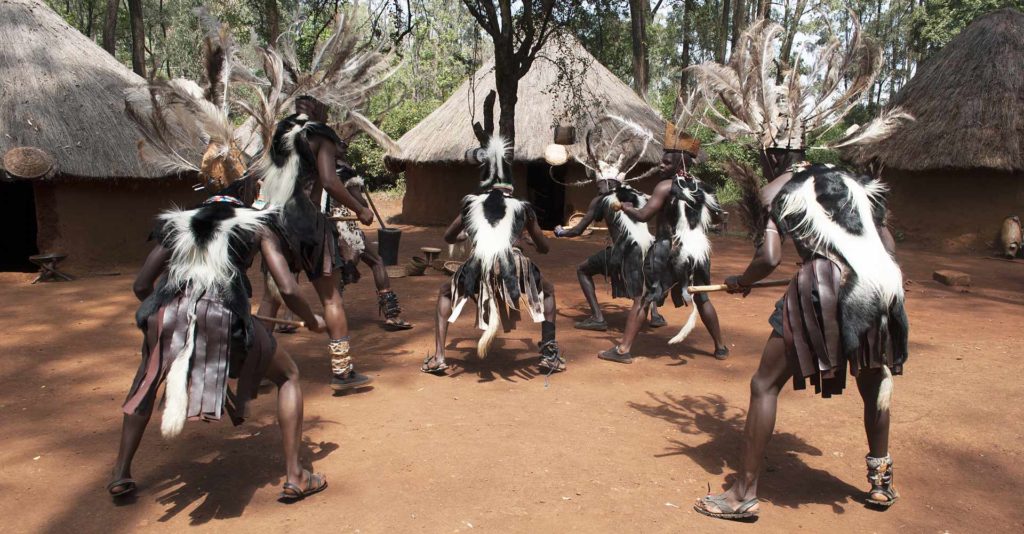

If you’d come to the Bomas of Kenya expecting to see a traditional Maasai dance performance you’d have been disappointed. Instead of the rhythmic chanting that typifies a Maasai dance, there’s a man in a cowboy hat playing an accordion: another holds a metal ring that he plays not unlike an orchestral triangle. It could be an American barn dance. And, instead of the gravity-defying jumps of the Maasai warriors, these dancers are paired into couples and follow a stately progression around the floor holding each other studiously at arm’s length.

The Mwomboko dance

If you didn’t know better you might be tempted to say that they’re dancing a parody of a waltz. And you wouldn’t be far wrong because this performance at the Kenyan Cultural Centre known as The Bomas of Kenya is an authentic rendition of the Mwomboko dance of the Kikuyu people. And it’s actually a tongue-in-cheek copy of the fox trot.

Surreal, elegant and quaintly romantic, the Mwomboko was born in the 1930s to 1940s era of colonial East Africa. Some say it was the result of the Kikuyu people having watched the British colonials dancing the waltz at their evening parties, many of which were rather colourfully decadent. Others say that the Kenyan foot soldiers of the First World War copied the dance from the waltzes, Scottish dances and fox trots that they watched their then colonial masters dance during the war. Whatever its origins, the Mwomboko became an instant hit amongst the Kikuyu and remains one of their most popular dances to this day.

But there’s a darker side to the history of Mwomboko, whose name evolved from the Kikuyu word for ‘eruption’. It seems that the Kikuyu were in the habit of weaving certain gestures into their traditional dances, such as the Murithingu dance, that spread anti-colonial messages. So, with sweeping finality, the British banned all such dances. It didn’t work.

In retaliation, the Kikuyu came up with the Mwomboko, which the British found hard to disapprove of. It was, after all, a seemingly innocent copy of their very own dance traditions. What the British didn’t know however was that the Kikuyu were not only using the Mwomboko to continue to pass on messages of rebellion but also to poke fun at the British.

Preserving Kenyan tradition

It’s a great story and the living embodiment of a fragment of history: it’s also just one of the many fascinating tales that lie behind the fifty or so dances preserved in the living archive of The Bomas of Kenya.

Established as a repository for the preservation of Kenyan tradition, The Bomas not only safeguards Kenya’s dance traditions, but also her music, cuisine, cultural artefacts and lifestyles. But it does so with a dedication to detail that would do credit to the most exacting of museums.

Every dance is researched in the region of its birth. Musical instruments are made according to ancient traditions using raw materials that are anthropologically correct and, when such things as colobus skins, kudu horns or monitor lizard hides are required, these are sustainably sourced from the Kenya Wildlife Service. Choreographers study the steps, musicians write down the music, designers replicate the costumes, local singers perform the songs, and very slowly the dance performance is moulded into a thing of ethnic perfection.

And even that’s not good enough for the eagle-eyed culture vultures of The Bomas. Because, when they have finally perfected the dance to the best of their ability, a delegation of community elders is invited down to Nairobi to assess the finished performance for precision of footwork, costume, lyrical enunciation and style of playing. And the elders don’t hold back when it comes to correcting anything that is not absolutely true to their fiercely protected ethnic history.

Traditional villages

The same attention to detail is brought to bear with the representations of the ethnic villages that dot the extensive grounds of The Bomas of Kenya. Laid out in exact replica of a traditional village, complete with grain stores, look-out posts and cattle enclosures, every hut has been hand-made by ethnically correct craftsmen and all the materials, even the mud, is regionally sourced. None of which makes for easy maintenance.

A Rendille hut, for instance, is built to withstand immense heat and profound drought, and struggles to remain standing amid the periodic deluges and chill of Nairobi. And then there’s the baboons. Situated immediately adjacent to Nairobi National Park, The Bomas of Kenya is a potent baboon draw, which is unfortunate because the baboons like nothing better than to methodically un-thatch the huts so carefully thatched by the cultural experts.

Cultural dance performances

Back on the dance floor, beneath the vast vaulted ceiling of the central pavilion, which was itself inspired by the traditional African hut, the Mwomboko has been replaced by a Kisii dance called the Rigesa, which originates from Nyanza. Now the musician plays a traditional obokano or 8-stringed lyre and instead of parodying the British, the dance tells the story of the Kisii migration from Uganda. And, if you watch carefully, you’ll see that representations of all the fearful animals the people met on their perilous journey have been woven into the dance – lions, elephants, leopards, buffalos and more.

Next comes a display of Chuka drumming, which originated amongst the Embu people of Eastern Kenya. The dancers, all male, bare-legged and muscled of arm are clad in provocatively short swaying rope skirts and hold huge cylindrical drums between their legs. The phallic inference is inescapable and history recounts that originally the dance was performed only for unmarried women in order that they might choose a husband. ‘We had to tone it down a bit for some of the performances,’ confides the choreographer in the darkness, ‘especially when we get a school party.’

There’s a 50-strong group of small school children in the audience – they’re rapt. On the front row, a diminutive boy is head-banging with all the conviction of a heavy metal addict. Two other little boys are thrusting their hips back and forth at each other in time with the drumming. It seems that the toning-down has not been entirely successful. Which is exactly as it should be.

The Bomas of Kenya - need to know

There are daily dance performances at The Bomas and guests are welcome to wander amongst the ethnic villages. The dancers can also be hired for special performances and there’s a burgeoning trend for weddings to be staged against the backdrop of a specific village accompanied by authentic ethnic dance and food from the onsite restaurant.

The Bomas of Kenya also offers a wide range of conference and meeting spaces and team-building pursuits.

Daily Performances:

Monday to Friday: 2:30 pm to 4:00 pm

Weekends and Public Holidays:

3:30 pm to 5:15 pm

For more information: www.bomasofkenya.co.ke

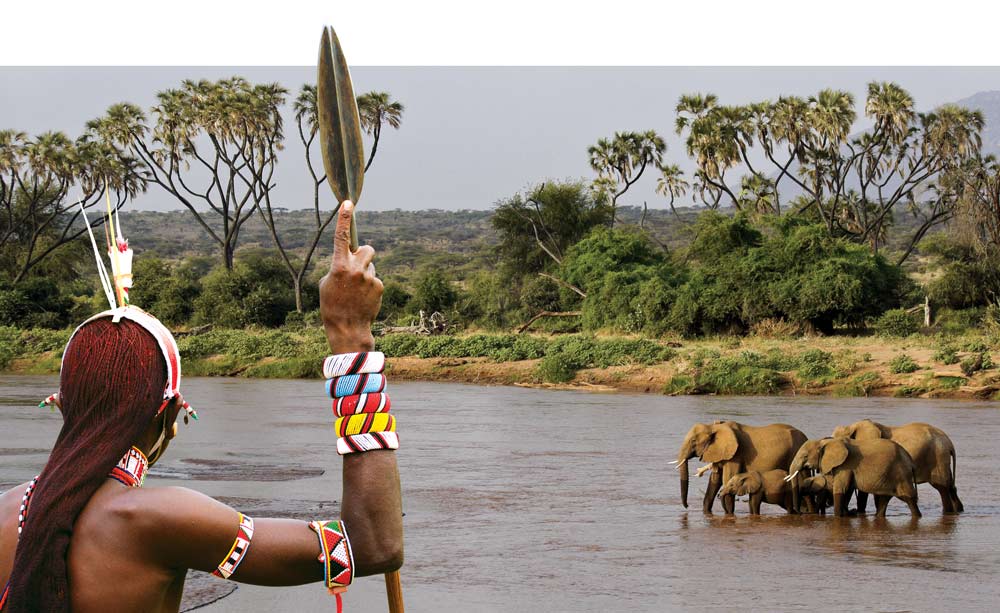

The Samburu

Kenya is a microcosm of Africa. People have migrated here from all over the African continent for centuries, and each incoming group has added to the cultural weave with a distinctive ethnic thread of their own. More brilliant than most, are the strands contributed by the Samburu, who live in the painted deserts of the north.

The butterfly people

It is said that the word ‘Samburu’ means butterfly, and there is much of the butterfly in these brightly coloured people, who flit across their harsh but beautiful landscape like so many exotic moths.

The young warriors, lithe and slender, may pride themselves on their beauty but they are renowned for their prowess as warriors. Unlike their cousins, the Maasai, the young Samburu men do not smear their entire body with ochre but make triangular designs down their chest and back. Wearing their traditional shukas wrapped tight around their waists, they apply elaborate paint around their eyes and accentuate the fineness of their elegant facial features with a beaded visor. Down their backs hang long braids of hair.

The meaning of beads

The girls, close shaven, wear intricate beadwork caps that loop around their eyes and nose. Their necks are encircled by hundreds of rings of beads, which undulate as they dance. Every woman’s collar is unique. Her first loops are given to her by her father. Later, her boyfriend may give her a collar as an indication of his love, but this must be returned when the girl is betrothed to the man of her parents’ choice. Now she will wear only scarlet beads until her marriage, and thereafter her beads will indicate how many children she has born. Lovers of butterfly yellow, brilliant blue and flaming pink, these days the Samburu seem to be conducting a love affair with the imported plastic flower. Both sexes like to top off their headdresses with either a daffodil or a tulip, worn in the style of a plume.

The Samburu are loosely related to the Maasai, being both nomadic and Maa-speaking. But the Samburu live in the arid desert lands to the north of Kenya between the jade waters of Lake Turkana and the muddy coils of the Ewaso Nyiro River. Herders of sheep, goats, cows and camels, the Samburu, like the Maasai, live primarily on blood and milk drawn from the necks of their living herds. Their clans are held together by age-group brotherhoods and their elaborate social customs have been handed down from centuries past.

The samburu and the elephants

Inhabitants of the dry, rock-strewn northern lands, the Samburu claim a close proximity with their fellow inhabitants, the elephants. Like the elephants, they are brave and loyal, their matriarchs are strong and their young men are cast out from the clan to prove their strength.

Indeed, it is said by the Samburu that at the dawn of time, they and the elephants lived side by side and helped each other. But one day a Samburu woman asked an elephant to go and gather sticks for her fire. The elephant returned with an entire tree that he had knocked over. ‘You stupid creature,’ said the woman, ‘I asked for sticks, not a tree. How can I make a fire with that?’ The elephant, much affronted, stormed out of the village catching up a hide that was drying in the sun and throwing it on to his head as he went. And ever since that time, the elephants have worn this hide as a pair of ears, which flap when they are annoyed.

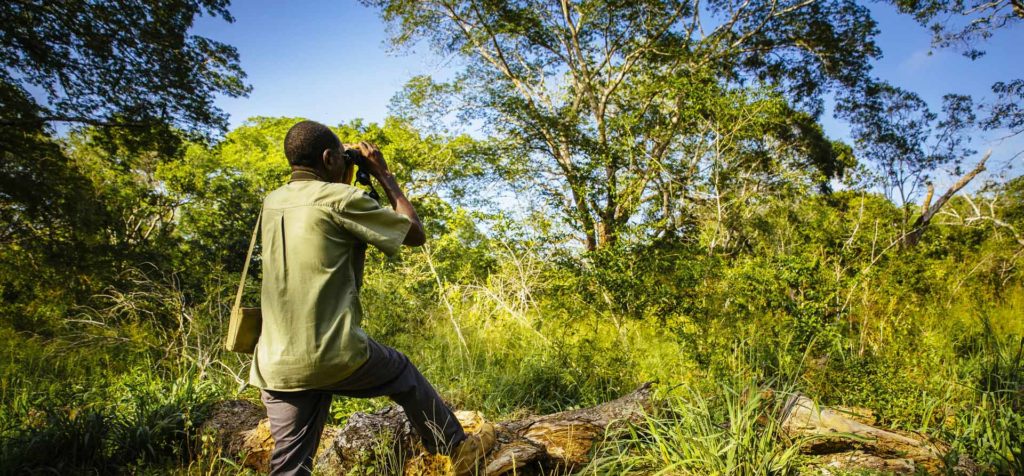

A visit to the Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve

Just a short drive from Watamu Beach is one of Kenya’s ecological gems, the Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve. Here you can wander the cool of this ancient forest and spot such rarities as the Sokoke Scops-owl, Sokoke bushy-tailed mongoose, the Ader’s duiker, the blotched genet cat and the caracal. You might also see bushbabies, Sykes’ monkeys, yellow baboons and vervet monkeys or representatives of the 230 species of birds and 263 species of butterflies.

To spot the famous Sokoke Scops-owl in the Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve you have to get up early. It’s nocturnal, on the IUCN red-list of endangered species, and traceable only by its whistle. And it’s only six inches high.

‘How early?’ we ask Jonathan, our guide, ‘around 4am,’ he says, ‘but if you want to see it I’ll send someone into the forest overnight. They’ll sit under its tree until you arrive.’ Owl-sitting? Well why not.

Elephant ahead! Simple - just take off your shirt…

Arabuko Sokoke solutions are colourful. Take the solution to the potential problem of encountering the forest elephants. The evidence as to their existence is everywhere. Their droppings litter the track, their tunnels dive off left and right into the dense undergrowth; and from time to time there’s an overturned tree across the track; and its roots have been wrenched off. So what happens if we meet an elephant on a track only broad enough for humans to walk two-abreast? The solution is scholarly.

‘Take a handful of sand and run it through your fingers’, says Jonathan. ‘Why?’ we ask. ‘To determine the wind direction’, he replies. We’re still mystified. ‘Elephants are very shortsighted,’ he explains, ‘so if you run in the opposite direction to the wind they won’t get your scent.’

We remain unconvinced. Is there not a more rapid response mechanism to a three-ton elephant on a tight track? Jonathan pushes his glasses up his nose. ‘Well,’ he says at last, ‘you could take off your shirt.’

Really? Now, why would we do that?

‘To throw at the elephant and so confuse its sense of smell,’ says Jonathan, ever the academic. There’s doubt amongst the female members of the party as to the wisdom of plunging bra-clad into the bush while elephant pursued, but we keep it to ourselves. And we’re rewarded by the assurance that the likelihood of our encountering elephants is zero: they have a marked aversion to human company. ‘You’ve got a much better chance of seeing a golden-rumped elephant shrew,’ says Jonathan. We’re keen. But we’re destined for disappointment because the forest delivers up her treasures slowly, and the shrew isn’t one of them. ‘You have to look for the little things,’ says Jonathan.

It's the little things

And so it is that we find ourselves engrossed in the do-or-die drama of a train of Matabele ants and a nest of termites. It’s epic. The ant-scouts scurry ahead; the soldier ants bring up the rear. They’re moving fast; and they mean business. In their mound, the fat white termites lie supine, blithely unaware of their approaching doom. The climax is superb: the nest is breached; the termites are carried off squirming between the shiny black pincers of the ants. What a denouement. And not only for the termites.

Looking down at our feet, we realize we’ve been ravished ourselves. Our shoes and socks are covered with tiny Chinese dragons with red, furry, crested tufts: they’re only caterpillars, but all the same… Then, looking up, we find we’re walking amid clouds of dancing butterflies, some as tiny as sugar cubes, others the size of coffee cups. Arabuko Sokoke is getting into her stride.

The bird whisperer

We follow the track through three distinct forest zones: in the first the branches arch over our heads and the air is heavy with the sultry camphor scent of mahogany. In the second, huge ferns edge the track. They’re cycads, the last surviving members of a species that flourished when the dinosaurs walked the earth. In the third, the air is filled with birdsong. A fish eagle screams overhead; a pair of tropical boubou sing an endless bubbling duet that ripples through the air like the gurgling of babies.

© John C. Avise

Suddenly Jonathan raises a hand for silence. He’s caught the distinctive call of a yellow-bellied greenbul singing deep in the bush. He mimics its three-note call to perfection. Fooled into thinking there’s a willing female on the track, the greenbul ventures ever-closer until he’s in the branches above Jonathan’s head. The man and bird exchange soft endearments. They’re mutually entranced. It’s a rare skill that Jonathan has perfected over many years of guiding. He’s good: very good. He’s a bird whisperer.

Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve - Need to know

The visitor centre of the Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve lies 1.5 km south of the Gedi/Watamu junction on the Malindi-Mombasa road. Here you can engage the services (for a small fee) of an official guide. Alternatively you can meander the tracks alone. The forest hosts 230 species of birds, 263 species of butterflies and such rarities as the Sokoke Scops-owl, Sokoke bushy-tailed mongoose, the Ader’s duiker, the blotched genet cat and the caracal. There are also bushbabies, Sykes’ monkeys, yellow baboons and vervet monkeys.

Our guide was Jonathan Baya – to book him email: jonathanbayakarisa.com

Samburu National Reserve – the painted desert

Hot and arid, Samburu National Reserve lies on the fringes of the vast desert that was once known as the ‘Northern Frontier District’, whose heat-scorched scrublands extend all the way to the jade-green waters of Lake Turkana and beyond.

The Reserve is an evocative cocktail of uniquely contrasting habitats. The landscape veers from stark cliffs and boulder-strewn scarps to lush swamps and muddy sandbanks. And from bone-dry bush to fronded riverine forests. A painted desert of brilliant colours, often set against dramatic skies, this is the realm of the indigenous succulent known as the ‘Desert Rose’, which bursts into exotic pink bloom amid the golden rocks and khaki scrub.

The plains of darkness

Known by the local nomadic tribe, the Gabbra, as ‘the Plains of Darkness’, Samburu National Reserve is essentially a lava plain theatrically punctuated by dry riverbeds (wadis), steep-sided gullies, rounded hills and harsh outcrops of ancient basement rocks. Roughly in its centre rises the stark outline of Koitogor Mountain.

The lifeblood of this dust-dry desert region is the the Ewaso Ng’iro River. It meanders in mud-brown loops throughout the reserve and is home to plentiful pods of snorting and chortling hippos. On its raised sandbanks immense Nile crocodiles bask, completely still, utterly camouflaged and menacingly patient. Amid the dense riverside thickets impala, common waterbuck and buffalo lurk.

The wildlife of Samburu

Prey to the harsh dictates of a dry country ecosystem, the reserve is prone to large variations in the animal populations as they move about in search of water and pasture. However, elephant encounters are common as large herds roam the reserve and they are best seen crossing the river, or returning to its banks at dusk to bathe.

The Reserve holds healthy numbers of lions, leopards and cheetahs as well as spotted and striped hyenas, bat-eared foxes and common genets. In the heat of the day, droves of banded and dwarf mongooses scurry in voracious hunting bands. At night golden and black-backed jackals prowl and aardwolves are occasionally seen.

Samburu is one of the few areas in Kenya where one can view the endangered Grevy’s zebra, which with its rounded ‘Mickey Mouse’ ears is notably different from its more common cousin, the Burchell’s zebra, which also roams the reserve. Other browsers of the thorny shrub include the magnificent reticulated giraffe - also endangered - and the rare Beisa oryx. There are also elands, impalas, Bright’s gazelles (the pale northern species of Grant’s gazelle) and the beautiful long-necked gerenuk, also known as the 'giraffe gazelle'. Elsewhere rooting warthogs and Kirk’s and Guenther’s dik-diks can be seen, and in small numbers both lesser and greater kudus.

Samburu's incredible birdlife

Samburu’s birdlife is so abundant that over 100 species can be spotted in a day. Perhaps most noteworthy of the sightings is the rare blue-shanked Somali ostrich. The most memorable perhaps is the flash of coral rump that flags the flight of the white-headed buffalo-weaver. Secretary birds are plentiful, as are bands of bustling helmeted and vulturine guineafowls.

Along the river, storks feed and sand grouse congregate at dusk. Both red-billed and Von der Decken’s hornbills are common. The Reserve’s characteristically rugged cliffs and starkly rising inselbergs provide the ideal habitat for raptors, which range in size from the tiny pygmy falcon to the giant martial eagle. Verreaux’s eagle owls also hunt the rivers.

Samburu National Reserve - Fact File

Altitude: 850-1,230 meters above sea level.

Area: 165 sq km.

Location: Samburu County, Rift Valley Region.

Distance from Nairobi: 320 km north-east of Nairobi.

Roads: 4WD is recommended for the journey to and within the reserve. 2WD vehicles with good ground clearance can be used outside the rainy seasons.

Gates: In addition to the main Archer’s Gate, there is Uaso Gate which leads to Buffalo Springs Reserve, and West Gate which leads to Wamba.

A Mara Balloon Safari

It is Kenya's most iconic safari experience: floating over the vast plains of the Masai Mara in a hot air balloon. There's simply no better way to see the wildlife and experience the scale and beauty of Kenya. A balloon safari is simply a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity; so we asked travel writer Jane Barsby to give it a try...

Early rise

A balloon safari starts early: at around five am. It’s inky black outside the flaps of your tent, and surprisingly chilly as you follow the night watchman’s wavering torch-beam to where an open-sided safari vehicle awaits you. Your fellow ballooners acknowledge you with a nod. It’s too early for wit. As the vehicle grinds its way across the savanna, the sky turns from indigo to lilac, and then to a heaven-tinged golden pink.

Arriving at the take-off point, you wonder why you had to get up so early. There’s plenty of activity from a team of men in overalls with torch-lights strapped to their foreheads. But the balloon itself lies limp as a rainbow-coloured pancake. A tangle of ropes streams out behind her and a huge basket is dragged into place.

A sudden roar shatters the grey blanket of dawn as a bank of burners fire up, and great dragon-breaths of fire lick into the swelling rainbow belly of the balloon. And very slowly, she begins to inflate and rise into the dove pink dawn.

All aboard

On the ground, the tempo changes. The watching ballooners stuff their cameras into their pockets, zip up their jackets and await the signal to hoist their chilled-stiff bodies into the high-sided basket. There are four compartments; four passengers in each. And it’s only when we’ve settled on our allotted benches that we realise what a rash thing we’ve done. The balloon, now fully inflated above us, is the size of two elephants. And she’s straining on her guy ropes, keen to be off. Do we really want to do this?

Benignly aware of the rising tide of panic among his passengers, the balloon pilot begins his spiel. He tells us in which direction we will be flying. He explains how the balloon can be steered by her guide ropes, and how she can dip down over the river and rise up again into the ether. Unease stirs when the landing is mentioned.

I shall say, ‘no more photographs’, says the pilot, looking round the white-pinched faces, ‘at which point you must put away your cameras, make sure you have nothing hanging around your neck, and take up your landing positions.’ He indicates the loops of rope that hang from the sides of the basket, ‘holding on to the landing ropes’. We nod grimly.

‘Right,’ says the pilot, pulling on a pair of thick leather gloves, ‘lets go.’ He pulls down on the aluminium bars that control the burners, the ground-men cast off the ropes and, with supremely silent grace, the great orange, blue and yellow bulb rises serenely through the morning mist, flirts with the tree tops, and sails away.

Flying at bird-level in the vastness of avian air space is a novel experience. So is skimming the tree panoply, flying past eagles nests, and peering down into glades where waterbuck browse. The experience has a curious dream-like quality. Only the great gouts of hot air belching into the balloon disturb the silence as we drift over the peacefully plodding elephant herds, and spy on the courtships and clashes taking place in the theatre of wildlife below. The hippos, drawn up on the banks of the river, look like so many well-browned sausages, and breakfast seems a long way off.

The balloon is curiously agile. She swoops down to skim the surface of the river; and hangs suspended over the flurry of hoofs and horns that is a leopard kill. She ascends rapidly and twirls like a lollipop at the pull of the the pilot’s guide-ropes. Far below, toiling ant-like in the massive shadow cast by the balloon on the landscape, the procession of support vehicles trails us.

What goes up must come down

‘Cameras away please,’ says the pilot suddenly, ‘take up landing positions.’

The balloon descends swiftly from on high: she’s moving fast across the scudding landscape. The ground draws ever closer: and looks ever harder. We brace, grab the ropes, clench our teeth, and accept our fate.

Bump number ONE – the basket merely kisses the ground.

Bump number TWO – the basket ploughs through the grass and then hauls herself up again.

And bump number THREE – we’re down.

All tearing, gouging motion stops. There’s a profound silence as we peep timidly over the side of the basket. Behind us, with a sigh of exhalation, the balloon topples away to lie flaccid on the khaki-coloured turf. We don’t know whether to whoop that we’ve made it. Or wail that it’s all over.

But it isn’t. Chilled fizz is proferred. A low table has been laid out on the plains, surrounded by erect Maasai spears and set around with folding stools. ‘Welcome to the most expensive breakfast in Africa,’ says the pilot. Now that's how to end a balloon safari.

Balloon safaris - need to know:

Your tour operator or Mara camp/lodge will be able to organise your balloon safari either before you arrive or once you're here. There are several reputable operators with impeccable safety records, including Governors Balloon Safaris, SkyShip, and Africa Eco Adventures.

Watch the balloon safari video from Governors' Camp, Masai Mara National Reserve.

Want Inspiration in your Inbox?

Sign up for FREE to receive our monthly e-newsletter with features

and ideas to help you plan your Kenyan adventure

© 2025 Kenya Holidays